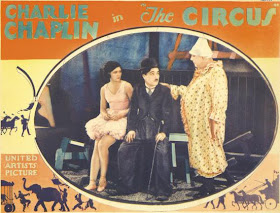

Wedged between two unequivocal classics, The Gold Rush (1925) and City Lights (1931), 1928's The Circus is Charlie Chaplin's undervalued "forgotten" feature-length Tramp film. In its day it was well received by critics and the public — in 1932 Variety listed it as the 7th highest grossing film to date, second only to The Gold Rush among Chaplin's films — yet Chaplin didn't mention it, not one word, in his autobiography, and he kept the film largely out of circulation for forty years.

Wedged between two unequivocal classics, The Gold Rush (1925) and City Lights (1931), 1928's The Circus is Charlie Chaplin's undervalued "forgotten" feature-length Tramp film. In its day it was well received by critics and the public — in 1932 Variety listed it as the 7th highest grossing film to date, second only to The Gold Rush among Chaplin's films — yet Chaplin didn't mention it, not one word, in his autobiography, and he kept the film largely out of circulation for forty years. The good news is that this comedy-romance, in which the Tramp wanders into a traveling circus and unwittingly becomes its star attraction, has received an upswing of attention in recent years. Chaplin fans who rediscover it tend to handle The Circus like a crated-up relic from a golden time, a Lost Ark newly opened to reveal treasures that previously had been glimpsed only in the occasional still photo or plot synopsis.

It turns out that The Circus is worth seeking out and deserves attention as representative of Chaplin's maturing work in feature films.

So why did The Circus get lost down the memory hole? One reason is that while it includes some of Chaplin's most memorable comic sequences, it serves up its simple story without the same levels of social realism and melancholic sentimentality that help distinguish its "Little Tramp" predecessors, The Kid and The Gold Rush, or its sublime successor, City Lights. A December 1927 issue of Picture Show quoted Chaplin describing The Circus as "making no attempt at great drama but ... intended purely and simply as a laugh-provoker." The Circus exists solely to be funny, so when compared to the films that bookend it, it's a lighter, slighter movie.

More likely, however, Chaplin entombed The Circus in his vaults for four decades because the two years of its production were utter hell for him. The production itself was plagued by one disaster after another. A laboratory error rendered the first month's footage unusable. A fire destroyed the vast circus-tent set, with water-damage further ruining the costumes and props.

Moreover, these were years when his private life didn't just unravel — it exploded and splattered the walls with a salacious, and very public, divorce suit brought by his 18-year-old second wife, Lita Grey. The grandstanding prosecutors aimed to destroy his career, à la Fatty Arbuckle, by smearing him as a threat to wholesome American values. Meanwhile, his mentally ill mother died, and the I.R.S. harassed him and seized his assets on charges of more than a million dollars in back taxes.

The result was an already-troubled shooting schedule interrupted for eight months while Chaplin spent time in New York and Europe to protect the incomplete footage and have a nervous breakdown. During these two years his hair, which had been lightly silvering, transformed to all-over white. It had to be dyed black once shooting resumed. (Watch The Circus closely and you can spot the "before" Chaplin and the "after" Chaplin intercut among the editing.)

In the face of such traumas, it's a miracle that the film is as warm and affecting as it is. And it's a testament to the public's love for Chaplin that the sordid airing of such dirty laundry failed to distance them from him. In David Robinson's best of all Chaplin biographies, Chaplin: His Life and Art, the chapter on The Circus spends several pages on the divorce suit alone, and Robinson states that no other public figure would have received such cleansing forgiveness.

Within moments of his arrival on the grounds of a down-on-its-luck circus, the broke and hungry Tramp is mistaken for a pickpocket. His chase from the police — and from the pickpocket's victim and the pickpocket himself — includes an ingenious gag with the Tramp and the pickpocket pretending to be clockwork automata to fool the cops. (See the "Mirror Maze" clip closer to the bottom of this post.) Once the Tramp and a cop run into the Big Top ring during a show, their antic chase delights the spectators, who believe it's not just all part of the act, it's the best part.

The show's actual clowns, a lackluster bunch, don't stand a chance against such accidental hilarity, so the ringmaster (Al Ernest Garcia, the Big Boss in Modern Times) hires the Tramp on the spot. Trouble is, the Tramp can't simply follow orders to "Go ahead and be funny," so he gets thrown into the ring to amuse audiences while he remains unaware of being laughed at.

The ringmaster is also the movie's black-hat stock villain, the abusive stepfather of the circus's bareback-rider (Merna Kennedy), the girl the Tramp falls for.

Just as predictably, there's a rival for the girl's eye, the handsome tightrope walker Rex, King of the Air (Harry Crocker, a socialite-turned-actor who Chaplin met through William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies).

After episodes involving a magician's tricks, that lion's cage, a mule, and stacks of dishes, the Tramp climbs up to the high-wire in a ruse to win the girl's affections. This climactic set-piece provides the nightmare image that first started Chaplin on the path to The Circus:

The Tramp wobbles in the middle of the tightrope when his support harness breaks away, leaving him stranded high above the crowd with only his wits — then he's besieged by a pack of aggressive monkeys who cling to him and pull down his trousers, revealing that he's forgotten his tights.

It would not be original to suggest that this scene provides a tidy metaphor for Chaplin's personal and professional vicissitudes at the time.

As an actor Chaplin is in fine form. The Tramp is as lovable and expressive as ever. His bittersweet semi-romance with Merna Kennedy hits the right notes, and we're in good, albeit overly familiar, hands when he can only watch as she falls for the dashing (and underdeveloped) Rex. By learning to wire-walk forty feet above the floor, then shooting hundreds of takes to get the big scene, Chaplin amped up his unsurpassed delicate pantomime to a climax comparable to Harold Lloyd's daredevil thrill-comedies from the same period.

His longtime cameraman, Roland Totheroh, beautifully captured some of the Tramp's finer poignant moments, such as the wistful closing iris on the lonesome figure strolling into the distance after the circus wagons have left him behind.

Still, for all its adroit and funny parts, there's a dissonance in The Circus that pokes at us. It's not just that the perfunctory romance feels largely disconnected from the Tramp's travails as a circus performer. (In every other Tramp feature, the main plot and the vagabond's amour with a pretty girl entwine more tightly than they do here.) Nor is it the overwrought, repetitive musical score that Chaplin composed for a 1970 reissue. (Like the voice-over narration he added to The Gold Rush in 1942, the score over-punctuates every moment, distracting from rather than supporting the visuals.)

Instead, The Circus possesses a disquieting undercurrent unique to the Tramp features. From a filmmaker who was rarely, if ever, subtle enough as a writer to be concerned about subtext, The Circus projects a sad, or maybe just weary, introspection circulating so between-the-lines from scene to scene that we can wonder if Chaplin himself wasn't aware of it.

In his essential survey of the early Hollywood comedians, The Silent Clowns, critic Walter Kerr puts his finger on the subtextual something under The Circus's skin, calling the film...

"...a workaday product of a comic genius at odds with himself.... With his stature elevated to near-Olympian heights by The Gold Rush, he had grown self-conscious as a comedian. In order to cope with the problem, he decided to dramatize it. He would make a comedy about the consciousness of being funny."As a meditation on the sources of a comedian's inspiration, the film pretzel-twists itself when the Tramp is supposed to be funny (to us) by not being funny (to the circus performers), then again funny (to the circus audience) by not being funny (to himself). There's something proto-postmodern in watching the Tramp being viewed by characters around him as an unaware "funny man" the way we in Chaplin's audience have been viewing the Tramp all along.

This sense of mirrors-reflecting-mirrors gets its literal expression in a terrific scene when the Tramp escapes the cops by dashing into a funhouse Mirror Maze. Its walls kaleidoscopically reflect so many images of the Tramp that he's confused about where to turn without conking into a hard surface. Holding a mirror up to one's self is a worthy purpose for any artist (and by this point in his career Chaplin definitely thought of himself as an Artist); a mirror image also distances us in the audience one more layer further from its subject, affording us a more detached or encompassing perspective. It would be interesting to know what Chaplin thought, as he watched The Circus from our perspective, while viewing himself viewing himself.

Whether by conscious choice or some subconscious working-through, the artifice of Chaplin's comedy is what this movie is about. Especially during the Big Top scenes, we're not watching the Tramp as much as we're watching Chaplin commenting on the Tramp, or on himself. Chaplin the Artist points at his creation and, like Magritte with his painting of a pipe that's subtitled "This is not a pipe," he prods us to view what's in the frame not only as a funny movie, but also as a self-inscribed editorial by its creator.

So it may be no coincidence that in terms of both style and content The Circus records a skip backward for Chaplin. That's not to say it's necessarily a regression or a stumble; rather, he seemed to retreat to the comfortable security blankets of the one- and two-reeler shorts that predated The Kid. In some ways Chaplin's The Circus is like Woody Allen's Stardust Memories, his reflexive self-observation in which Woody's line, "We like your earlier, funny movies," flashes subliminally among the frames.

Chaplin never did shake off the nostalgia that froze him in a state of arrested personal development. And as a filmmaker his attachment to What Used To Be kept him willfully, stubbornly, egotistically standing at the train station that he helped build; meanwhile the filmcraft bullet-train pulled away without him. He still had masterpieces within him — City Lights, Modern Times, and to a mixed degree The Great Dictator, but as early as The Circus we see hints of the backward-looking self-consciousness that would hobble Limelight and other later films.

As Kerr puts it, there's just enough brilliance along the outer edges of The Circus to compensate for the troubled preoccupation at its center. When the contemporary critics welcomed it, some acknowledged that it did not continue the uptick in Chaplin's artistry seen in The Gold Rush, and several noted its harking back to the "earlier, funny" Tramp shorts.

A few years ago I happened to be staying at the Roosevelt and found a life-size bronze statue of the Tramp sitting inside the hotel's entry foyer along Hollywood Blvd. I understand it has since been removed during a remodel. Pity I didn't get a chance to bid on it and set it up in my movie room, where it would be welcome indeed.

By the way, if you're interested in checking out The Circus on DVD, go for the MK2/Warner Home Video Chaplin Collection edition from 2004. The restored imagery looks quite good and the soundtrack — Chaplin's 1970 reissue orchestral score, complete with his syrupy song, "Swing Little Girl," which he sang with cloying earnestness over the opening titles — comes in two remastered options — the original mono and a 5.1 surround remix.

Better yet are the extra features that fill out the film and its production saga:

Chaplin Today - The Circus (26 minutes) — Before expanding on the personal and professional difficulties Chaplin endured while making The Circus, François Ede's documentary opens with a biographical look at Chaplin's professional beginnings in the English music halls and Fred Karno's touring vaudeville troupe. Ede shows us the "inebriate" act that made young Chaplin an audience favorite, and finds connections between those old stage routines, Chaplin's early shorts, and The Circus. The voice-over narration includes clips from a vintage Chaplin interview. Shooting The Circus involved routines as well as an entire restaurant scene that Chaplin eventually did not use, and that footage receives special attention. So does the surviving tightrope-walking scene, which illuminates the fastidious director's perfectionist nature. This featurette also brings in Yugoslav/Bosnian director Emir Kusturica, who — while holding a cigar the size of a canoe — zooms his filmmaker's eye onto the techniques Chaplin employed when crafting The Circus.

Deleted Sequence (10 minutes) — Here's a treat for Chaplinologists. While production on the main stage was suspended because of fire-and-water damage and reconstruction, Chaplin devised a restaurant scene with himself, Merna Kennedy, Harry Crocker, and 'Doc' Stone, who played twin prize fighters (thanks to double-exposure). Chaplin shot the sequence with the intention of inserting it into the final cut. The rest of The Circus was strong enough to work without it, so the restaurant scene never made the edit. Here it is, a self-contained one-reel short all by itself. The scene opens with a clever bit as the Tramp practices his tightrope routine on an upturned rake before escorting Merna along a still rural-looking Sunset Blvd., where they meet Rex. When the Tramp tries to upstage Rex's gallantry, he instead turns a matron's arm-load of wrapped fish into a sidewalk calamity. After they arrive at the restaurant, the Tramp connives with a bullying fighter to impress Merna, with similar results. The footage is well preserved. No audio.

October 7-13, 1926 (26 minutes) — In this series of outtakes shot during a week of The Circus's production, Chaplin improvises and revises the restaurant scene as the camera rolls. The varying takes give us a clear look at the director-actor's working methods. (Film historian and preservationist David Shepard deserves thanks for assembling the various takes for the previous Laserdisc edition of The Circus.)

Hollywood Premiere (6 minutes) — The Circus's L.A. opening occurred at Grauman's Chinese Theatre (a short walk from Chaplin Studios) on January 26, 1928. This silent newsreel footage records real circus performers hired for the hoopla, plus celebrities such as W.C. Fields, Cecil B. DeMille, John Barrymore, and Jackie "The Kid" Coogan stepping up to the radio broadcast microphone at the theater's entrance.

Music: John Adams/Kronos Quartet, Gnarly Buttons & John's Book of Alleged Dances

Near at hand: Notebook with line: "Street sign - corner of Taken and Not Taken"