"It was intoxicating!" — Rod Taylor as the Time Traveler, The Time Machine, 1960

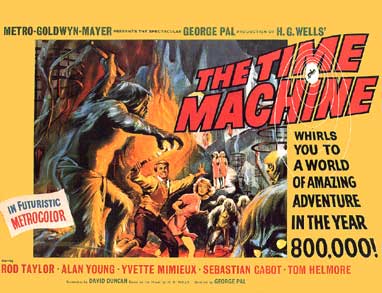

As I mentioned at the top of my last post, on the 1936 H.G. Wells movie Things to Come, I've been meaning to blogify the 1960 George Pal production of Wells' The Time Machine for a while. So here I sit, the day after Thanksgiving, having just slid the DVD out of the player, marveling at how enjoyable The Time Machine still is, how well it holds up in its fiftieth year.

I often find that movies I enjoyed in my youth are better off in my memory than when I revisit them again. In this case, I may like the movie even more now. Or at least I appreciate it more, recognizing its craft and acknowledging its charms with movie-watching experience well beyond the gosh-wow of my back-then kid self. That gosh-wow is still there for me, almost surprisingly, making The Time Machine, for all its Saturday-morning-cereal-box flavor and pop, still one of my favorite vintage science-fiction adventure films.

In the intervening years I've backfilled my understanding of where Pal's movie came from by reading and loving Wells' seminal novel (available online here, here, and here). So I'm compelled to start there when chatting about the movie, much the same way I pulled various threads together when I posted about The War of the Worlds from Wells' novel to Pal's 1956 movie and two hypothetical Hitchcock versions. In each case, the differences and similarities between the book and the movie, and what they say about the times they emerged from, are fascinating (well, to me at least).

The Time Machine: 1895

The Time Machine: 1895The Time Machine, the debut novel of a young, ideological Herbert George Wells, reflects its author's bleakly dystopian, anti-capitalist worldview in a Darwinian cautionary parable. Wells, after all, didn't set out to write merely an entertaining page-turner. A self-made social reformer who climbed up and out from brutal working-class poverty, Wells sought to deliver a trenchant "If this goes on" message.

In the book, the unnamed Time Traveler tells of his voyage to the year 802,701, a time in which humanity has degenerated into two species sculpted not by God but by nature's indifferent efficiency. The delicate and placid Eloi — descendants of the wealthy and privileged — live in edenic bounty and "feeble prettiness" on Earth's surface (in the space that had been the Time Traveler's home, in fact), unaware that they are merely bred and fed to become food for the Morlocks — descendants of the working class who have devolved into cannibalistic subterranean brutes feeding off the do-nothing, illiterate "Upper-world people."

In the book, the unnamed Time Traveler tells of his voyage to the year 802,701, a time in which humanity has degenerated into two species sculpted not by God but by nature's indifferent efficiency. The delicate and placid Eloi — descendants of the wealthy and privileged — live in edenic bounty and "feeble prettiness" on Earth's surface (in the space that had been the Time Traveler's home, in fact), unaware that they are merely bred and fed to become food for the Morlocks — descendants of the working class who have devolved into cannibalistic subterranean brutes feeding off the do-nothing, illiterate "Upper-world people."The Time Traveler is an observer only, speculating and theorizing about what forces brought mankind to such straits. "It seemed to me that I had happened upon humanity upon the wane. The ruddy sunset set me thinking of the sunset of mankind. For the first time I began to realize an odd consequence of the social effort in which we are at present engaged." There's a moment in chapter 4 where he climbs to the crest of a hill and finds a sort of golden throne, "a seat of some yellow metal that I did not recognize, corroded in places ... the arm-rests cast and filed into the resemblance of griffins’ heads." There he sits and surveys "the broad view of our old world under the sunset of that long day." But his position as an authority figure in this strange world is merely figurative. He is not an adventurer-savior.

Near the novel's end is a beautifully rendered scene set eons later still. Here the final, gasping breath of evolution, human and otherwise, is embodied in a single tentacled creature on a beach beneath a bloated red sun at the twilight of the world. It's a Dying Earth scenario lit by loneliness and failure and Ozymandian futility.

To Wells' fellow fin-de-siécle Victorian intelligentsia, the contemporary social issues magnified for easy dissection in The Time Machine (and throughout Wells' career) pointed to a human race doomed by its own animal nature and trapped within the engine of capital-N Nature, which is — as he later described the minds of his Martian invaders — "vast and cool and unsympathetic."

As in the 1960 movie, the fraught, disheveled Time Traveler spins his tale to a cluster of (mostly) disbelieving dinner guests — the narrator, the Editor, the Medical Man, the Psychologist, the Very Young Man, and Filby. The final moments of the final chapter see the Time Traveler spiriting himself back to the future, leaving the narrator...

...waiting for the Time Traveller; waiting for the second, perhaps still stranger story, and the specimens and photographs he would bring with him. But I am beginning now to fear that I must wait a lifetime. The Time Traveller vanished three years ago. And, as everybody knows now, he has never returned.Wells doesn't tell us the Time Traveler's ultimate fate in the vasty deeps of Time. However, perhaps he does provide a hint: In Chapter 2 the narrator mentions the mysterious Silent Man, "a quiet, shy man with a beard," at the dinner table. As Glenn "DVD Savant" Erickson (a movie-watching kindred spirit of long correspondence) says at his site:

"The Silent Man is obviously the Time Traveler himself, returned at an advanced age. Older but perhaps wiser, he's there just to contemplate his younger self. His motive has to be guessed at, and it is easy to read into his blankness anything one wants."This sly nuance by Wells, if that's what it is (and I do believe it is) pleases me mightily — this suggestion not just of some self-directed circularity in the Time Traveler's life, but also of Time's potential mutability, and therefore the possibility, however slim, that the bleak, pointless future the Time Traveler witnessed can be avoided, undone. At least that's my read on it. I am a "this time machine is half full" kind of guy.

The Time Machine: 1960

The Time Machine, the movie produced and directed by George Pal fifty years ago, reflects a very different time and a very different audience. While Wells' story is social class commentary wrapped within a stark narrative fable, Pal's movie is a brightly colored sweetmeat with all the indicting political ideology of a buttered scone. It's a Boy's Own adventure complete with handsome square-jawed inventor undertaking a journey through the Fourth Dimension to a new world complete with monsters, fisticuffs, rescues, escapes, and a keen awareness of our protagonist's superiority to the poor benighted heathens in his midst. He is every inch the adventurer-savior. Along the way, the memorable orchestral score by Russell Garcia hits all the right stirring emotional notes.

The Time Machine, the movie produced and directed by George Pal fifty years ago, reflects a very different time and a very different audience. While Wells' story is social class commentary wrapped within a stark narrative fable, Pal's movie is a brightly colored sweetmeat with all the indicting political ideology of a buttered scone. It's a Boy's Own adventure complete with handsome square-jawed inventor undertaking a journey through the Fourth Dimension to a new world complete with monsters, fisticuffs, rescues, escapes, and a keen awareness of our protagonist's superiority to the poor benighted heathens in his midst. He is every inch the adventurer-savior. Along the way, the memorable orchestral score by Russell Garcia hits all the right stirring emotional notes.Wells' story ends with a sigh at Mankind's ultimately insignificant place in an indifferent cosmos. Pal's ends with an optimistic romantic hero returning to the future to lead the Eloi out of their Dark Ages and into a new Enlightenment of learning and questioning and, one presumes, other proper English virtues.

One can imagine Wells — righteously angry at Mankind's foibles and predilection for self-destruction — riding his Time Machine to our present and viewing the fruits of Mr. Pal's labor in the Wells vineyard. What would be Wells' reaction? In a word, he would plotz.

But does that make Pal's movie a poor adaptation?

Not at all. Certainly not if you're 15 years old, as I was when I first watched The Time Machine on a weekend afternoon between one TV program and another. I loved it. So I admit to a certain prejudice while saying that, after watching it again decades later, I still love it.

Not at all. Certainly not if you're 15 years old, as I was when I first watched The Time Machine on a weekend afternoon between one TV program and another. I loved it. So I admit to a certain prejudice while saying that, after watching it again decades later, I still love it.Is it hokum? Sure, much of it. The titular machine itself, as envisioned by Pal in one of the classic pieces of pre-CGI model-making, is perhaps symbolic of the movie as a whole: It's a charmingly magical fantasy contraption; its apparati are all aglitter with polished brass finishes and faceted crystal; the rider's compartment is cozy with red velvet cushions and tasteful Victorian filigree scrollwork. It's clean and functional, here and there a little gaudy, and isn't stained by any over-abundant motor oil of logic. It does, however, take you where you want to go.

The movie stars Rod Taylor as the Time Traveler, now named George. Taylor soon after went on to provide the voice of Pongo in One Hundred and One Dalmatians and then reached his first career peak as the leading man in The Birds. His appearance as Churchill in Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds was, for me, one of that film's numerous pleasant surprises.

Likewise, Taylor's solid performance as George is one of the many likeable elements in The Time Machine. He's a true Pal protagonist — a driven, earnest man of learning who still has what it takes to beat the baddies and get the girl, a model for males throughout the Western world. Even when fighting a mob of Morlocks in their cavernous lair strewn with the remains of cannibalistic feasts, Taylor's hair is never mussed — and that looks exactly right.

Alan Young co-stars as David Filby, George's best and most loyal friend. His is the voice of restraint that tells George there are things Man was not meant to know, that he should be content to live in his own present world, that one should not tempt fate in the name of upstart wanderlust. He provides the conservative counterpoint to George's idealistic questing:

Alan Young co-stars as David Filby, George's best and most loyal friend. His is the voice of restraint that tells George there are things Man was not meant to know, that he should be content to live in his own present world, that one should not tempt fate in the name of upstart wanderlust. He provides the conservative counterpoint to George's idealistic questing:"I have no desire to tempt the laws of Providence, and I don't think you should. It's not for Man to trifle with.... There is something to say about the common-sense attitude to life. If that machine can do what you say it can do, destroy it, George! Destroy it before it destroys you!"Filby chides George with such kindly, brotherly concern that when we learn what becomes of Filby in the near future the movie offers one of its few moments of touching poignancy. Young, in fact, plays two characters, the second being Filby's son Jamie, whom George meets in the future. But more on that shortly.

The inevitable MGM add-on love interest is delivered by Yvette Mimieux as the young Eloi woman Weena. Granted, perhaps you shouldn't watch the movie with a female friend possessing strong feelings about the depiction of women on screen (Elizabeth's imitation of Weena is a scream). Vapid and childlike, Weena single-handedly sets back 800,000+ years of women's progress. She is the evolutionary end of all "dumb blonde" jokes, and apparently retains an excellent hairdresser.

This being 1960 Hollywood, Mimieux is just dandy as the fantasy girlfriend of earnest inventors and 15-year-old boys everywhere. She's not just pretty. Better yet, she's innocent and compliant — and, we can infer, unfettered by all those socially imposed sexual hangups that are so anti-evolutionary. (C'mon, you don't have to be 15 to imagine what's waiting for George, our Competent Man avatar, when in the end he chooses to leave our time and return to Weena's side. "To help build a new world" my ass.)

To the credit of Pal and screenwriter David Duncan, many of the bolts and rivets of Wells' plot remain intact — in particular, the opening scene (set in a Christmas-card London, New Years Eve 1899) of George demonstrating his bric-a-brac model Machine for his disbelieving friends (a fine supporting cast headlined by Young, Sebastian Cabot, and Whitt Bissell).

What's added provides little bulk to the rest of Wells' plot, so the story here is pretty thin. Still, the scenes of George witnessing the passing years and decades of the 20th century are perhaps the most interesting part of the movie.

When people talk about the special effects in Pal's Time Machine, this is very likely the sequence they're talking about. Remember that we're talking about a movie made a generation before CGI and computer-controlled camera work, the "In my day we walked ten miles through snow up to our beltloops to get to school" days of cinematic fantasy-making. In a sequence that today strikes you as either brilliant or cheesy (or both) depending on your sensibilities, George observes the accelerated rush of Time and Fashion by the amusing time-lapse changes occurring on a department store mannequin. The Time Machine's stop-motion and time-lapse trickery won 1961's Academy Award for Best Special Effects, and while they may look a tad dated today, they still display an economy and purpose that exceed even some of today's bloated and less mindful CGI extravaganzas.

When people talk about the special effects in Pal's Time Machine, this is very likely the sequence they're talking about. Remember that we're talking about a movie made a generation before CGI and computer-controlled camera work, the "In my day we walked ten miles through snow up to our beltloops to get to school" days of cinematic fantasy-making. In a sequence that today strikes you as either brilliant or cheesy (or both) depending on your sensibilities, George observes the accelerated rush of Time and Fashion by the amusing time-lapse changes occurring on a department store mannequin. The Time Machine's stop-motion and time-lapse trickery won 1961's Academy Award for Best Special Effects, and while they may look a tad dated today, they still display an economy and purpose that exceed even some of today's bloated and less mindful CGI extravaganzas. Other scenes that exist only in the movie have George making brief stops during his initial journey forward. These scenes set up what can be considered Pal's equivalent of Wells' narrative diatribe. However, in 1960 Cold War insecurities had trumped Victorian class consciousness for an audience's attention. Pausing to look around in 1917, George meets young James Filby (Alan Young again), a soldier newly returned from "the front." When Filby tells George the fate of Filby Sr., he buttresses the Time Traveler's disgust at modern man's instinct for warfare. When George departs this world at war he immediately arrives in another, stopping in 1940 during a blitz bombing of his London neighborhood.

Then in 1966 (six years in the movie's future) he arrives just in time to hear the air raid sirens and to encounter young Filby Jr. again, now an old man in a silver radiation suit leading others to the neighborhood fallout shelter because of an "atomic satellite zeroing in." Mushroom clouds ("the labor of centuries, gone in an instant") and the violent response of Planet Earth herself almost prevent George from reaching his Time Machine and propelling himself far, far into a future that he is sure will have evolved into an enlightened utopia free from our primitive barbarism.

"One vast garden," he says of his initial explorations when he finally arrives. "At last I found a paradise!" It isn't long before he discovers just how wrong he is on that point.

It's the 20th-century Cold War adornments — air raid sirens, underground shelters, and the phrase "all clear" — that set up the world George finds in the year 802,701.

Pal's extrapolation isn't as thought-provoking and weighty as Wells', and it's Wells' that arguably has aged better. Give Pal's vision its due, though. As he did four years later with another fantasy fave of mine, The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao, by weaving a thread, however thin, of contemporary commentary into his movie, Pal's Time Machine steps up a rung from what studio executives probably considered little more than children's fare. And for us today watching the movie, it provides a look back to a time when the possibilities of bomb shelters and air raid sirens and atomic annihilation were real enough to make Pal's Eloi and Morlocks, if not possible, then at least unnervingly plausible.

The rest of the movie proceeds briskly in expected pulp magazine fashion. The vacuously innocent — and universally blond — Eloi enjoy their sunlit existence of mindless frolicking and consuming, without knowledge of reading, writing, or even fire.

"What have you done? Thousands of years of building and rebuilding, creating and recreating so you can let it crumble to dust. A million years of sensitive men dying for their dreams. For what? So you can swim and dance and play!"Meanwhile the few surviving books crumble to dust untouched and unread. Necessary exposition comes from the Talking Rings (voiced by the ubiquitous Paul Frees), mechanisms so ancient and underpowered that they can only hint at the history of the preceding 800,000 years. George frowns at the story they tell, while Weena looks on smiling at the incomprehensible toys.

Down below, the degenerate, nocturnal Morlocks tend the chugging machinery and surface periodically to harvest the "fatted cattle" Eloi for their own grisly larders.

To all this our hero arrives, explores, endures, pontificates, and punches Morlocks in the snoot, all with his best girl by his side.

Naturally enough, he becomes both a savior and role model action hero for the Eloi, who learn from him that one can rise up and thump one's oppressors with fists and aggression, and that active self-determination is the first step toward freedom (and, let's be waggish, toward starvation and privation resulting from the wreckage of what had been a comfortable economic system, if like the Eloi you're ignorant of all that cannibalistic feasting and stuff). Watching him set this essentially alien civilization aright, I can't help but consider how on-the-money Taylor would be have been if cast as Star Trek's Capt. Kirk six years later.

Don't worry about the built-in story conveniences. Expect to chuckle out loud at least once. So the Eloi speak perfect English even if they can't spell "social Darwinism." So the chubby, green-skinned Morlocks' winky-blink lightbulb eyes look silly. So Taylor saves humanity by blowing up an underground complex roughly the size of a city block. George Pal knew what he wanted and accomplished it with aplomb and his own period style and verve, just as H.G. took care of his own creative goals and audiences. Pal replaced Wells' grim prognostication with a sense of wonder that's still effective today.

Pal's Time Machine is simplistic but avoids being merely simple-minded. It's a puff pasty. Tea with jam and bread. The movie makes an interesting bookend for Pal's earlier and darker War of the Worlds, his even looser adaptation of a Wells novel. Playing compare-contrast between them justifies a double-feature evening.

|

| George Pal |

Then, to give you a peek into the kind of motion picture Wells felt more at home with, cap the evening with Things to Come (1936), for which Wells wrote the screenplay. That one is more impressive in terms of "vision" and conceptual scale, plus keeps Wells' tendency toward ideological pontification intact. On the other hand, while Things to Come may have more thoughtful meat on its bones, I can guarantee that you'll have a better time with Pal's adaptations. So I recommend sandwiching the real Wells between the other two, finishing on a high note with The Time Machine.

The current DVD of The Time Machine (and Amazon's "on demand" streaming) adds a fine 50-minute behind-the-scenes documentary, The Time Machine: The Journey Back, hosted by Rod Taylor and featuring Alan Young and Whit Bissell. Produced in 1993, it focuses on the production and special effects, with special attention given to what ultimately became of the Time Machine prop itself (talk about salvation from the brink of oblivion!).

The current DVD of The Time Machine (and Amazon's "on demand" streaming) adds a fine 50-minute behind-the-scenes documentary, The Time Machine: The Journey Back, hosted by Rod Taylor and featuring Alan Young and Whit Bissell. Produced in 1993, it focuses on the production and special effects, with special attention given to what ultimately became of the Time Machine prop itself (talk about salvation from the brink of oblivion!).Then the documentary takes an unusual, warm turn near the end with a charming vignette, a real "Journey Back" in the form of a mini-sequel to the movie made thirty years before. Rod Taylor's George — much older yet still virile — returns in the Time Machine to his laboratory. The resulting scene between George and Filby (a suitably gray-haired Young) offers a touching coda that honors both characters and the movie they helped bring to life.

I like to think that even ol' H.G. himself would approve.

Music: a Fats Waller compilation

Near at hand: Shakespeare figure standing in conversation with a tin robot figure.