|

It's also one of my "desert island" films. Three various Robby the Robot figurines on my office shelves look upon me as I type this. Recently I traded in my old DVD edition for the new Blu-ray disc. A poster, framed, looms large in my movie room. I have visited Seattle's Science Fiction Museum and stood before their life-sized talking Robby and gone "Wow!" That's also where I spotted one of Anne Francis' costumes from the film and exclaimed, "Holy cow, she was tiny."

It's the classic that, although more than fifty years old, is still my favorite spaceships-rayguns-and-alien-worlds movie to come out of Hollywood. Them's fightin' words in some quarters, but I'm standing by them.

In 1956 with Forbidden Planet, MGM did for pulp science fiction yarns what it had done for musicals four years earlier with another personal fave, Singin' in the Rain. The studio took the stuff audiences loved, gave it that high-polish MGM razzle-dazzle, and produced an enduring best-of-breed favorite, a CinemaScope spectacle that's terrifically entertaining, smartly written, memorably cast, briskly paced, and production-designed to the hilt.

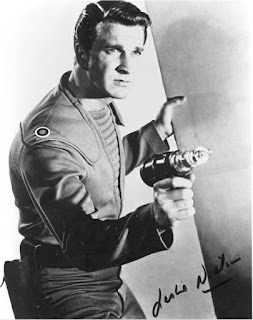

Instead of Gene Kelly's tap shoes or Debbie Reynolds' pertness, here we get Nielsen as a proto-Captain Kirk, plot points lifted with an Amazing Stories spin from Shakespeare's The Tempest, special effects photography that still knocks our socks off, Hollywood's most famous robot before Star Wars' less interesting droids, and (the stuff space kids' dreams are made on) leggy Anne Francis ably modeling miniskirts a decade early.

It has aged remarkably well, and any dated elements — that great flying-saucer design of the starship, the crew's baseball-cap uniforms, the terrific "electronic tonalities" score, the opening narrator ballyhooing mankind's "conquest" of space, the casual Rat Pack-era sexism — add a quaint yesteryear charm to the film's robust retro-future vibe.

The contact points with The Tempest are at best cursory, but they're not immaterial. Shakespeare's Prospero becomes Walter Pidgeon's Prof. Morbius, stranded on an island (planet Altair 4) that he has shaped into his own private dominion. With him is his beautiful and educated yet "terribly ignorant" daughter Altaira (Anne Francis) — obviously Shakespeare's Miranda given a glossy fan-mag update. Having known no human beings besides her father, she delivers a rewrite of Miranda's lines upon encountering her first other humans:

O, wonder!Altaira turns the analogous moment into a breathy, purring approbation:

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world,

That has such people in't!

"I've always so terribly wanted to meet a young man, and now three at once.... You're lovely, Doctor. Of course, the two end ones are unbelievable." (TCM clip)

Rounding out the dramatis personae, quasi-magical Robby takes the position of Prospero's servant spirit Ariel. Shakespeare's antagonist "monster," the native Caliban, gets supersized here into the murderous Monster from the Id, whose power literally emanates from the planet itself. Earl Holliman's "Cookie," the ship's lowbrow, conniving cook and connoisseur of genuine Kansas City bourbon, stands in for Shakespeare's drunkard clowns Stephano and Trinculo.

Nielsen's by-the-book space skipper is an analog for The Tempest's young Ferdinand in only one way — he falls hard for Morbius-Prospero's daughter, sailing away with her at the end of the tale — but it's a big enough point of contact to carry us through. Unlike the shipwrecked survivors in The Tempest, the "unbelievable" men aboard United Planets Cruiser C-57D arrive at Morbius' planet with purpose and under orders, not tempest toss'd by Morbius-Propero's willful magicks. However, later in the story, the Id Monster — a manifestation of Morbius' psyche — smashes vital equipment aboard the ship, effectively marooning the crew until repairs are made (meanwhile, several crewmen are slaughtered). So that's something.

MGM's top brass never considered Forbidden Planet an A-list project. Nonetheless, the art department (headed by the mighty Cedric Gibbons), in cohoots with the film's writers (Cyril Hume from a story by Irving Block and blacklistee Allen Adler) and director (Fred M. Wilcox), treated the material and their potential audiences with respect, all in the name of creating something better than the zipperback monster fare so common at the time. Ten years before Star Trek used Forbidden Planet as a template for an entire franchise of boldly-goingness, and 21 years before Star Wars microwaved Joseph Campbell and Saturday matinee shoot-em-ups, here's a movie that proved you can do good things with "that outer space stuff" without dishing up more invading aliens or other fast-turnaround juvenilia.

The down side of that extra effort was a budget that made a big busting kaboom! sound at nearly $2 million during a year that already saw plenty of red ink in the studio's balance books. Add the fact that Forbidden Planet didn't come close to, say, Singin' in the Rain's boffo box office, and you can see why the film stands out as a uniquely lavish one-off for science fiction at the time.

Today, after two post-Star Wars generations that have seen science-fiction become as mainstream as westerns in the '50s, this one continues to rank in the top tier of Hollywood's contributions, arguably besting other period watersheds such as The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Thing from Another World. It impresses us with its scale, its relatively grownup plot, and its determination to employ its wall-to-wall visuals and sure-footed cast to the service of crackerjack storytelling. Forbidden Planet balances the tawdry with the sublime, mixing its color-comics gee-whiz sci-fi tropes with aspirations more thoughtful and engaging than most "sci fi" films before or after.

Forbidden Planet sure has served its duty as an inspiration to fifty years' worth of subsequent filmmakers. It's a safe bet that if Forbidden Planet had never been made, there would be no Star Trek, any generation. And without the Star Trek pop phenomenon to prove that voyages to "strange new worlds" had audience appeal, would Star Wars have ever seen frame one? Robby became the standard-bearer for screen robots for decades, and he (or at least big pieces of him) was a recognizable touchstone for a generation of TV-addled genre junkies. No Robby, no C-3PO?

Trivia that makes me go boing!: According to his Wikipedia page, the voice talent who "spoke" for Robby, Marvin Miller, is the voice of the film's trailer, was Narrator for the Oscar-winning cartoon Gerald McBoing-Boing, a PA Announcer in Robert Altman's MASH, and the Narrator in the 1982 TV comedy Police Squad, which starred — boing! — Leslie Nielsen in his first outing as Detective Frank Drebin.

The movie's plot hangs on a simplistic but effective interpretation of Freud's theory of the Id, the primal brute we all carry inside us no matter how evolved our so-called civilization has become. Soon after Commander Adams plants his ship on planet Altair 4 — the most beautiful spaceship landing ever filmed, by the way — what's supposed to be a routine rescue mission turns into a nightmare of destruction and murder. The cause is an all-powerful monster, a giant roaring beast that's visible only when engulfed in a force-field blaze and the energy bolts from the crew's ineffectual blaster guns.

At the center of the mystery stands Dr. Morbius, one of the lone survivors of an expedition decimated by the malevolent force twenty years earlier. Imperious, arrogant, and relishing his solitude on "his" world, Morbius lives alone on the planet with his robot manservant, Robby, whom Morbius "tinkered together" like "child's play" with knowledge far beyond "Earth's combined sciences."

Also sharing his isolation is his daughter, Altaira.

Altaira is beautiful and brilliant, but socially inexperienced. So her naiveté on matters of "basic biology" is more than just a pheromonal attractor for the spacemen suddenly surrounding her. And it's clear that after being "locked up in hyperspace for three hundred and seventy-eight days," these "eighteen competitively selected, super-fit physical specimens with an average age of 24.6" step out of the ship a mite horny. Hey, seriously, after more than a year who wouldn't be?

Naturally, after some token resistance a romance develops between the protective, virile commander and Altaira.

To a degree that would have Freud himself reaching for his pipe, her heretofore innocent maturity is also the catalyst for subconscious energies Morbius is teasing from the vast subterranean machines left behind by the alien Krell, an enigmatic super-race whose miles-wide cavernous machines apparently contributed to their overnight annihilation thousands of centuries ago. (TCM clip)

Morbius' testimonial for his "beloved Krell" is worth repeating:

"In times long past, this planet was the home of a mighty and noble race of beings which called themselves the Krell. Ethically, as well as technologically, they were a million years ahead of humankind. For, in unlocking the mysteries of nature, they had conquered even their baser selves. And when, in the course of eons, they had abolished sickness and insanity and crime and all injustice, they turned, still with high benevolence outward toward space. Long before the dawn of man’s history, they had walked our Earth, and brought back many biological specimens."

That bit about how they "conquered even their baser selves" stands out. Not to go all Post-Colonial Theory or anything — but let's just say that the whole plot turns on how even the mighty Krell's "baser selves" refused to stay "conquered" once the Krell "instrumentality" set them free.

The exemplar of Morbius' own hubris is that he, even with his artificially boosted intellect, can't recognize (or at least consciously accept) the bald truth — that his own baser self, his subconscious possessiveness of his own "little egomaniac empire" that includes Altaira, has given form to things unknown. His "twin self" has reincarnated the Krell's destroyer, "sly and irresistible and only waiting to be re-invoked for murder." Morbius can't accept the reality even when it's literally burning down his door. Only Commander Adams sees clearly enough to explain to Morbius, in his most Shatneresque moment, that he may have high benevolence piled to the adamantine steel rafters, but that means exactly diddly-squat to the "mindless primitive" that's "more enraged and more inflamed with each new frustration" to the point of killing even his daughter to "punish her for her disloyalty and disobedience."

Adams' words sink in. Morbius submits to the evidence. "Guilty! Guilty!" he cries. "My evil self is at that door, and I have no power to stop it!" That is to say, as Prospero says of Caliban, "This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine."

Hoo boy. So much for 'Take Your Daughter to Work' Day.

In the film as we've known it for years, Altaira's alluring influence on Adams and his crewmen — not to mention on her father — is handled with precisely tuned between-the-lines understatement.Adams' words sink in. Morbius submits to the evidence. "Guilty! Guilty!" he cries. "My evil self is at that door, and I have no power to stop it!" That is to say, as Prospero says of Caliban, "This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine."

Hoo boy. So much for 'Take Your Daughter to Work' Day.

However, the deleted footage available on the DVD and Blu-ray discs makes it clear that originally the undiscovered country of her virginal womanhood received more direct attention. Snipped from the final release print was dialogue between Doc Ostrow (Warren Stevens) and Capt. Adams, with the good Doc trying to explain Alta's seemingly magical rapport with her animal friends on Altair 4. He references the myth of the unicorn and the girl's "maiden purity." Well.

Later, Doc points out that she possesses an "exceptionally fine human brain in a totally unawakened female body." Adams replies, "Of course, it'll be a pity when the time comes that she has to lose a gift like that." Gift schmift. Were it not for the editor's scissors, the tropes of Fifties-era female "virtue" would have collided with the hormonal imaginations of every male in the audience already picturing the "awakening" of that female body.

Suddenly the film's sense of wonder takes on a whole new prurient vividness. Had those lines remained, Forbidden Planet might have ushered in a generation's puberty — or boosted enrollment in the space program — years before America was ready.

Music: John Lee Hooker

Near at hand: A gift for Wendy.