So I visited the site and knew right away that here was someone I wanted to be like. I wanted to be that smart when it comes to movies — new movies and (especially) those from earlier decades and social eras; famous classics as well as rarities as obscure as Grant Williams at the end of The Incredible Shrinking Man. And I wanted to write like him, with that authoritative yet personable style, that relaxed and unforced sense of humor, and that way of making you think about — not just react to — movies and move-making in new ways.

I discovered that he's also an astute film historian and a contributor for Turner Classic Movies and is a go-to expert on Film Noir. His day job as a film and video editor has earned him an Emmy nomination. Glenn produced the restoration of the original "lost" ending to the Cold War sci-fi noir classic Kiss Me Deadly. Early in his career he worked behind the scenes on two Spielberg films, 1941 and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. His coolness quotient just kept going up.

|

| The Gulliver-like head of Glenn Erickson, summer 1977. |

| That stretch of road some months later. |

Plus, it turned out that he's just a hell of a nice guy. An erudite film buff who can write and a gentleman to boot.

Somewhere during all that, Glenn and I became friends. Well, in that Internet way at least. For years we've been emailing each other links and jokes and pictures and mutual appreciation of each other's work. When I was a producer-writer for Film.com, my first "get" was Glenn as a weekly contributor there. Our correspondence has continued to the point where I feel comfortable calling him a "friend" even though we haven't yet actually met in person. Next time I get down to L.A. or he makes it north to Seattle, we'll finally clink glasses in 3D space.

And twice a week his DVD Savant column remains a never-miss destination for me.

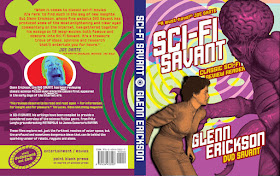

All that throat-clearing is by way of full disclosure. For this post isn't just a personal reminiscence. I'm here to beat the drum for Glenn's new book, Sci-Fi Savant (Wildside Press) and I acknowledge that I'm not exactly an unbiased critic when I say you should click over to Amazon right now and buy a copy before you leave Open the Pod Bay Doors, HAL.

This "classic sci-fi review reader" collects his thoughts on 116 science fiction movies. It presents an entertaining thumbnail history of the genre in chronological order, from Fritz Lang's seminal Metropolis (up to date with the most recent restoration) through to Pixar's Wall-E and James Cameron's Avatar (where Glenn recognizes its cinema precursors as broader and deeper than just the obvious Dances With Wolves).

In between he covers decades of science fiction milestones (e.g., Things to Come, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Forbidden Planet, 2001: A Space Odyssey), not to mention some worthy millstones (rubber-monster and exploitation fare such as Gorgo, Attack of the Crab Monsters, The Brain from Planet Arous, and Teenage Caveman). He treats grade-A major studio releases and B- to Z-grade giant-muto-slime-bug flicks as illustrative segments of the same continuum, as cultural snapshots that reveal as much about us in the audience as about whoever it was behind the camera.

He gives fresh perspectives to big-deal classics that have been written about to death over the years. For instance, his pieces on Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still, Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, and Cameron's Avatar have refocused the way I view those films and those filmmakers.

Meanwhile he waves the flag for under-appreciated masterworks such as Val Guest's Enemy From Space, a.k.a. Quatermass 2, from Hammer Films in 1957.

|

| Cosmic Journey, USSR, 1936 |

"Catching up with Ikarie and and other Eastern Bloc films made during the Cold War," Glenn says in his thoughtful Introduction, "is like discovering a new wing in a favorite museum."

|

| Red Planet Mars |

He also reminds us that more modern films aren't immune to their own unspoken assumptions that, like the arrow in the FedEx logo, become unmissable once they're pointed out by someone paying attention. His pages on RoboCop and Starship Troopers, films I have dismissed with a disparaging wave of my hand, inspire me to give them a close rewatch for possible reappraisal.

He also reminds us that more modern films aren't immune to their own unspoken assumptions that, like the arrow in the FedEx logo, become unmissable once they're pointed out by someone paying attention. His pages on RoboCop and Starship Troopers, films I have dismissed with a disparaging wave of my hand, inspire me to give them a close rewatch for possible reappraisal. This book is a casual sample platter, not an end-all or definitive final word on the subject. A conversational, non-academic read such as this should only be so thick, so editorial adjudication led to some omissions I'd love to see here just to get Glenn's take on them — e.g., Slaughterhouse Five, Sleeper, Brazil, Alien, 12 Monkeys, The Matrix, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Primer, and Moon. Of course, I can get all those and hundreds more at Glenn's site, plus enough farther-reaching articles and essays to fill a couple dozen books this size.

Besides, any arguable gaps are more than offset by the new material written exclusively for Sci-Fi Savant, and especially the chapters that have introduced me to films I'd previously never known about (and I'm no neophyte in this territory). I'm talking about the BBC's documentary-like post-nuke extrapolation The War Game from 1965; the Czech doomsday drama Konec srpna v Hotelu Ozon (The End of August at the Hotel Ozone); Gorath, Ishiro Honda's Japanese angle on the apocalyptic "worlds in collision" scenario; and the Film Board of Canada's 1990 short animated To Be ("a gem of a film, a philosphic wonder in miniature").

That said, the "anti-2001" German agitprop film Der große Verhau (The Big Mess) from 1970 sounds so unwatchable I wonder if it's really worth the page space.

| The President's Analyst |

Glenn deploys his sense of humor with a light touch. Good thing, too, because as he states in his Introduction, as with any genre "the overall appeal of sci-fi can't be judged by its finest works alone." So he takes several dips into some of the, let us say, less artistically sophisticated movies that represent the field. Even here, though, Glenn refreshingly doesn't resort to easy snark and insult humor. He is no fan of Mystery Science Theater spitball-shooting, so even when his opinion of a given movie is less than laudatory, his professional regard for the artisans and working stiffs behind the scenes never stoops to petty mockery. That's not to say he isn't averse to a nip from the sarcasm bottle now and then. Re Irwin Allen's Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea:

"Director Allen shows his opinion of [Barbara] Eden's acting talent by saving his only non-eye level, non-boring interior shot for a CinemaScope close-up of Eden's derrière gyrating to goldbrick Frankie Avalon's trumpet music. Eden's off-screen husband Michael Ansara wanders about cradling a puppy and mumbling deranged prophecies about the end of the world. The annoying radio announcer with the Jersey accent is none other than our producer Irwin, saving a buck."My favorite, though, is an isolated pullquote spoofing the colorful terminology we hear exclaimed in David Lynch's Dune: "For surely he IS the Cuisinart Hat Rack!"

Other points of interest include extended essays on 1953's Invaders from Mars ("a personal fascination since childhood") and the three-hour original European cut of Wim Wenders' 1991 Until the End of the World. His write-up on George Pal's The Time Machine takes a side-step into an aspect of the source novel that has nothing to do with the film, but it's an interesting digression nonetheless, one that has made me rethink and appreciate anew H.G. Wells' cleverness in his original story. I like that Glenn opened the fence wide enough to include Walt Disney in Space and Beyond, a three-hour collection of Tomorrowland-themed television "infotainment" programs that from 1955-59 sold America on the vision of space travel as a new Manifest Destiny.

Other points of interest include extended essays on 1953's Invaders from Mars ("a personal fascination since childhood") and the three-hour original European cut of Wim Wenders' 1991 Until the End of the World. His write-up on George Pal's The Time Machine takes a side-step into an aspect of the source novel that has nothing to do with the film, but it's an interesting digression nonetheless, one that has made me rethink and appreciate anew H.G. Wells' cleverness in his original story. I like that Glenn opened the fence wide enough to include Walt Disney in Space and Beyond, a three-hour collection of Tomorrowland-themed television "infotainment" programs that from 1955-59 sold America on the vision of space travel as a new Manifest Destiny. For readers watching at home (which means pretty much all of us) entries also add information about their respective DVD or Blu-ray viewing options. As "DVD Savant" since the 1990s, Glenn has been championing movies' presentation on home video, so here he provides info on transfer quality, commentary tracks, featured extras, and so on as relevant. It's a handy addendum when it comes to avoiding inferior bargain-bin public domain DVD editions, or as a reference source for buffing up your own home cinema library.

While I'm placing Sci-Fi Savant on the shelf as a worthy companion to Bill Warren's essential Keep Watching the Skies! American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties and Phil Hardy's The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction, Glenn's less formalized approach to the subject appeals to the casual movie-watcher as well as the already-bitten aficionado. Plus it has the advantage of being significantly cheaper than those coffee-table-crunchers and quite a bit easier to read in bed.

My only plaint is that the overall text could have used one more pass under an editor's eye to clear out the occasional typos and other infelicitous line-level mechanics. I'm a stickler for that sort of thing. (Insert Annie Hall quote: "...because I'm anal." Annie: "That's a polite word for what you are.")

Now, what was it I recommended way up there? Oh, yes — click over to Amazon right now and buy a copy.

Music: Philip Glass

Near at hand: Kai sleeping by my office door