Such a pleasure in a gem discovered came to me with The Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena), Víctor Erice's hypnotic and haunting Spanish film from 1973.

Beginning, significantly, with the imagination's On switch, "Once upon a time...," Spirit is set in a tiny, isolated Castilian village in 1940, soon after Spain's traumatizing civil war. It's a place and people clouded by the implicit background of Franco's repressive dictatorship. Franco's censorious fascist regime still held a cracking, gasping stranglehold when Erice made The Spirit of the Beehive, so looking for Erice's coded subversive critiques of the Franco government is one of the film's headier pleasures. (The superb two-disc DVD edition from Criterion helps us today watch the film in the context of what a Spanish filmmaker could and could not overtly say in his work at the time.)

However, our first approach to it should not be as a social commentary. It's a more immediate, oblique, and richer experience than that. As we follow it through the black, old-soul eyes of six-year-old Ana (Ana Torrent), The Spirit of the Beehive is a visually striking sketch of childhood at the place where childhood fantasy and bullet-hard reality come together. How those two opposites blend and shape one another gives us a graceful, lyrical masterpiece wound around one of the most natural and engrossing performances by a child actor I've ever seen.

The Spirit of the Beehive also turns out to be a poetic appreciation for the power that "movie magic" can have on us, especially when we're young. The triggering event arrives on a truck with a traveling exhibition of James Whale's Frankenstein. After the town crier alerts the villagers to their annual movie-going surprise, everyone arrives at the old town hall carrying their chairs and eager for whatever the roving picture-shower has in his battered tin reel-cans.

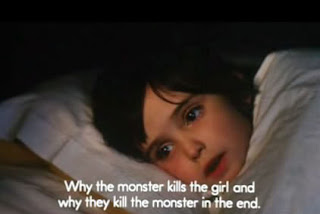

To Ana and her older (and evidently disturbed) sister Isabel (Isabel Tellería), Boris Karloff's Monster is literally the stuff that dreams are made on. That night, lying awake in their adjacent beds, their whispered conversation starts with Ana's curiosity about the Monster and the deaths she saw in the movie. Isabel tells her that the Monster is a real spirit that lives in an abandoned farmhouse nearby.

The scene captures exactly the way kids talk when grownups aren't around, their cadences and rhythms, and their easy, fantastical lies that bend the outer world through a child's interior lenses. It compels Ana to wish up Frankenstein's Monster at her moonlit window and, furtively at first, at the farmhouse. There she encounters an injured soldier who has jumped from a passing train (presumably one of the Spanish maquis guerillas resisting the Franco regime) and she tends to him as if he is the "spirit" she imagines.

But when government soldiers find and execute him, Ana — like Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird — must reposition her interior lenses for a world that continually redefines "monster." When Ana runs away and, alongside a lake in a forest at night, finally comes face to face with Frankenstein's Monster, it's just one of a hundred resonant ambiguities that feel rich with meaning if only we can suss it out. With a film this beautiful and well-crafted, reading the scenes for meaning and metaphor becomes a pleasure rather than a chore. Erice doesn't condescend by spelling it all out for us. Instead, he invites a mutual involvement that engages us directly, one-on-one, to lift The Spirit of the Beehive onto a level of artisanal filmmaking that defies reductive interpretation and pigeonholing.

Through its spare, elliptical script sculpted by strong performances and exquisite cinematography, the film layers on questions and mysteries. A harsh moment between Isabel and her pet cat, and later another between Isabel and Ana, tell us that there's something broken and cruel inside the elder sister. Is it that Frankenstein and the Death within that film have pushed her in a dark direction separate from Ana's, or did the civil war's brutal reality shape her first?

What meaning does beekeeping, and the translucent artificial hive he has constructed, hold for their wealthy father (Fernando Fernán Gómez), who's immersed in a treatise on his bees' industriousness in a land where the people are held motionless? (Kevin Wilson at thirtyframesasecond is worth quoting here: "Is the imagery of the community of bees and windows in beehive shapes reflective of community under Fascism - ordered, organised, but devoid of individuality or imagination? Is Ana the only hope, the only individual in a homogeneous society?")

Who is the man that their distracted, beautiful mother (Teresa Gimpera) writes letter after letter to — a lover-soldier captured and held in France? The girls' father and mother exist in their own self-imposed universes, interacting so little that for most of the film each may not even be aware of the other's presence.

Are the girls simply girls expressing their own interior lives as only children do, or is Erice showing a choice of two futures available to post-Franco Spain — one wide-eyed and open to magical possibilities, the other calloused and indifferent to suffering?

Here's a film that benefits from rewatching, each time adjusting our own interior lenses. And I love movies like that, that do that, that do that to me. It's doesn't happen often enough, and the older I get the more I look for it — honestly, the more I feel I need it.

Whatever The Spirit of the Beehive can be said to be "about" (and I don't have an answer pinned to the corkboard on that yet), there's something in there that I dig above all:

The people who populate Ana's world — her fractured family, her town (and by extension Spain under Franco's thumb), all seemingly stunned into somnambulance by that devastating civil war — exist, like the bees in their hives, as isolated units, potentially visible to each other but walled off behind the glass of rote routine and functionary movement, forced into pinched-off lives as much by self-induced inertia and introversion as by political repression and suppression. And what single source of outside stimulation shakes up that dreary order, adds some spirit to the hive, at least for Ana?

The people who populate Ana's world — her fractured family, her town (and by extension Spain under Franco's thumb), all seemingly stunned into somnambulance by that devastating civil war — exist, like the bees in their hives, as isolated units, potentially visible to each other but walled off behind the glass of rote routine and functionary movement, forced into pinched-off lives as much by self-induced inertia and introversion as by political repression and suppression. And what single source of outside stimulation shakes up that dreary order, adds some spirit to the hive, at least for Ana?A movie. Frankenstein, one of my favorites.

When asked at Entertainment Weekly if The Spirit of the Beehive was an inspiration for his Pan's Labyrinth, director Guillermo del Toro replied: "It could be. Not consciously. I nevertheless must admit that Spirit of the Beehive is one of those seminal movies that seeped into my very soul. Night of the Hunter, Whale's Frankenstein, Bunuel's Los Olvidados, etc... The girl in Cronos was deliberately patterned after Ana Torrent in Spirit."

On a purely cinematic level The Spirit of the Beehive is a treasure box of discoveries. Its biggest impression comes from the honey-colored light and exacting compositions of Luís Cuadrado's cinematography, which evokes the Dutch master painters, particularly Vermeer. His church-window lighting and magic-hour landscape portraits of the desolate, windy Castilian plain and the village's dun-colored homes create a world that's so dreamlike we can wonder if, to Erice, it's an entire country that's waking to whatever its imagination conjures up.

Criterion's DVD gives us The Spirit of the Beehive in a typically exemplary presentation. The anamorphic image (1.66:1 OAR) is pristine and fresh-looking. The Dolby Digital 1.0 audio is likewise faultless. The language, of course, is Spanish, and the English subtitles are easy to read and appear to be translated very well.

Headlining the substantial supplements are a pair of strong documentaries on Disc Two. The Footprints of a Spirit (48 mins.) features director Víctor Erice, producer Elías Querejeta, co-screenwriter Ángel Fernández-Santos, and now-adult actor Ana Torrent. Shaped around a showing of Beehive in the tiny village of Hoyuelos (pop. 92) where it was filmed, this production reminiscence points up the film's rich visual elements and the mood-piece effects the director strove for. "Instead of scenes," Erice says, "I called them 'emotional spaces.'" Erice also discusses the difficulties artists faced under Franco's oppression.

Headlining the substantial supplements are a pair of strong documentaries on Disc Two. The Footprints of a Spirit (48 mins.) features director Víctor Erice, producer Elías Querejeta, co-screenwriter Ángel Fernández-Santos, and now-adult actor Ana Torrent. Shaped around a showing of Beehive in the tiny village of Hoyuelos (pop. 92) where it was filmed, this production reminiscence points up the film's rich visual elements and the mood-piece effects the director strove for. "Instead of scenes," Erice says, "I called them 'emotional spaces.'" Erice also discusses the difficulties artists faced under Franco's oppression. Next is Víctor Erice in Madrid (48 mins.), an informative interview with the director, who acknowledges the influence of John Ford on his work. Two shorter but no less enlightening interviews are with Case Western Reserve film scholar Linda Ehrlich (16 mins., highly recommended) and actor Fernando Fernán Gómez (11 mins.).

Packaged with the discs is a 12-page booklet with an essay by film scholar Paul Julian Smith.

Music: Marianne Faithfull, 20th Century Blues

Near at hand: glass jar filled with translucent rubber balls