It's good. I just like having a reason — finally, after how long? — to type that.

It's good. I just like having a reason — finally, after how long? — to type that.Midnight in Paris is not one of cinema's "greats," or even one of Woody Allen's ultimate postmortem Top 5 bests in my estimation. (In my book that Top 5 would be Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, Manhattan, The Purple Rose of Cairo, Love & Death, Zelig, Broadway Danny Rose, Sleeper, Radio Days, Stardust Memories, Bullets Over Broadway, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Shadows and Fog.... What, you really want only five?)

But Midnight in Paris, it is good, and that's enough for me at this point, my bar having been ratcheted down so far over the years. I'd call it his best since Bullets Over Broadway in '94. And for this life-long, card-carrying Woody Allen fan-devotee-acolyte-aficionado*, one bludgeoned to dispirited peevishness by more than a decade of one subpar Woody Allen movie after another — that it didn't outright piss me off is a blessed relief.

Midnight in Paris moves along with a jaunty rhythm and pace that feels as natural as filtered water in an artificial stream in an over-landscaped garden. Still, that's a welcome change after so many of Allen's prior films since the '90s that sputtered fitfully like the rusty flow from a clogged faucet.

Granted, Mighty Aphrodite ('95), Everyone Says I Love You ('96), Deconstructing Harry ('97), and Sweet and Lowdown ('99) are on my DVD shelves because I generally like them, albeit sometimes more for their parts than for the sums thereof. But Celebrity in '98 was that unforeseen, unspeakable thing I thought I'd never experience: an utterly unwatchable Woody Allen movie. Since then, so many of them have ranged from bland and unrewarding to Oh please no just stop!

The Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Hollywood Ending, Melinda and Melinda.... Okay, generously, each had one or two good bits or moments, maybe, some fleeting wisp of the old Woody glitter that actually seemed to make the surrounding drudgery even worse. But even with strong casting they were instantly forgettable while you were watching them. The wretched Anything Else ('03) ruined Christina Ricci for me.

The widely praised "comeback" film Match Point (2005) was a big step back up toward the light. But while it struck me as a film engineered with watchmaker precision, it came off as just as coldly mechanical. Its follow-up, Scoop ('06), slid me right back to the exasperating ho-hummery. I didn't even bother with his next one, Cassandra's Dream.

Vicky Cristina Barcelona ('08) didn't outright wow me but it did give me hope. That is, until Whatever Works ('09) had me throwing up my hands and blowing out the votive candles in front of my framed Annie Hall one-sheet poster.

For the past several years I've despaired at the thought that the comic who said "On the plus side, death is one of the few things that can be done as easily lying down" would discover whether or not that's true before proving that he had one more good movie left in him. Not a great one necessarily, not a crowning masterpiece, although wouldn't that be a fine way to go out? Just one more that didn't leave me summarizing my response with a shrug and a sour-apple frown and a non-ironic "Meh."

And now?

I nod to Dana Stevens at Slate who said it this way: "Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris ... is a trifle in both senses of the word: a feather-light, disposable thing, and a rich dessert appealingly layered with cake, jam, and cream. It's the first Woody Allen movie in a long time that feels good going down, even if it doesn't stay in your stomach for long afterward."

Right from the beginning Midnight in Paris mines past Woody Allen films: obviously Manhattan in its opening montage and Frommer's Travel Guide settings, and the superior The Purple Rose of Cairo in this story's origami fold of that film's core fantasies. Also familiar are Midnight's themes (celebrity worship, inspired art vs. commercialism, mismatched romance, infidelity), its narrative set-up and structure, his characters (no, not characters, really: single-stroke character sketches), their relationships and interactions, their dialogue, even line readings.... There may be nothing here that you can't find several close analogs for in his previous work.

The key, though, is that he recycles good stuff from his peak years, c. 1977-90. If you've seen two or three or four of his films from those years, then went into Midnight in Paris with no clue whatsoever who'd made it, arriving late enough to just miss the opening credits, within five minutes — ten, tops — you'd recognize it as a Woody Allen film. But hey, if someone's going to do a loving pastiche of Golden Age Woody Allen films, it might as well be Woody Allen.

The core of Midnight in Paris has apparently been percolating within Allen for nearly 50 years. During his early career as a standup comic in the 1960s, his great "Lost Generation" bit gives us Allen reminiscing about his time in Europe hanging with Gertrude Stein, Picasso, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway punching him in the mouth. (Its audio is YouTubed here.)

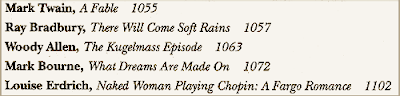

Then in a 1977 New Yorker story, "The Kugelmass Episode", an unhappy humanities professor learns to transport himself at will into works of fiction and interact with his revered literary characters. A few years ago one of my own stories was anthologized alongside it in a university literature textbook.

In a

Then again, by the end of Midnight in Paris Allen upends that notion by revealing the folly of nostalgia and saying, essentially, "Fuck that." At last, here's his wistful sigh accompanying an acceptance that the past, personal as well as historical, is another country best viewed from a safe distance. Perhaps our Golden Age really is always right now.

Owen Wilson: Always likeable and reliable. Here he's the expected Allen proxy, yet he manages to wrest the role out of the shadow of past Allen-alikes and make it all his own. It's "the Woody Allen role" played with commitment by Wilson, not by Wilson "doing" Allen. Gil's Paris-in-the-1920s fantasies are an extension of the Allen we've known for decades in films and comic prose, and Wilson's performance lets us experience those fantasies with blithe acceptance of the make-believe.

All the same, Gil's not much of a character. Like everyone else in the film he's written with the depth of a business card, and it's a credit to Wilson, not Allen, that Gil isn't unlikeable on that point alone. Gil's personal "journey" is practically defined by its low stakes and its brazenly painless wish-fulfillment resolution, complete with luminous Léa Seydoux inevitably positioned just so for him at the fade-out.

Rachel McAdams: I've liked her ever since Slings & Arrows and it's fine to see her breaking out to A(ish)-list status. Too bad her strident Inez, Gil's shrewish fiancée, is written to be more Plot Device than a fully realized human being. Whatever does Gil see in her to the point of being engaged to marry her (moreover, gaining her horrid Tea Party Republican parents as in-laws)? What does she see in him, frankly, given who she is and what she wants? We come away without a clue because both Inez and Gil are drawn so superficially.

I have to wonder: after seeing McAdams take a lead in Guy Ritchie's Sherlock Holmes and now in Midnight in Paris: Did her agent maneuver a contract clause requiring directors to frame glamor shots of her ass? Not that that's a bad thing. But once again it's as noticeable as a Pepsi logo product placement ad.

I have to wonder: after seeing McAdams take a lead in Guy Ritchie's Sherlock Holmes and now in Midnight in Paris: Did her agent maneuver a contract clause requiring directors to frame glamor shots of her ass? Not that that's a bad thing. But once again it's as noticeable as a Pepsi logo product placement ad.Corey Stoll doesn't play Hemingway. He plays Kevin Kline 20 years ago playing Hemingway. And he's terrific at it. He speaks only in the distilled parodic, two-fisted Hemingwayese we might imagine (rather, that Gil imagines) was "Papa's" honed conversational style, and it cracks me up just sitting here remembering it. But not for a minute did I believe that was actually Hemingway.

Meanwhile, Kurt Fuller as John, Inez's father, channels Alan Alda from Crimes and Misdemeanors and Everyone Says I Love You.

Adrien Brody: "Dah-LI!" Heh.

Michael Sheen as Paul, the pedantic prick — "If I'm not mistaken," I've known this guy in numerous forms over the years. I confess there were times when I've been this guy. His position, however, as the other half of the Inez Plot Device exists only to hand Gil a gold-laminated Get Out of Jail Free Card. Inez's affair with him exists simply to, lickety-split, absolve Gil and end his relationship with her. What should be a powerful scene in the film instead simply grates with its lazy utility.

Marion Cotillard as Adriana — Yes, please.

It's nice to see Quai de la Tournelle on the Left Bank, under the arches of Notre-Dame, used again as a setting. It's where Goldie Hawn danced on air in Everyone Says I Love You, and here it's the spot where Zelda Fitzgerald (Alison Pill, inspired) stages what's probably only the latest in a series of public freak-outs.

Speaking of seeing, the striking cinematography (an Allen hallmark) by Johanne Debas and Darius Khondji, coupled with Anne Seibel's production design and art direction, provides a high percentage of the film's appeal, and it's interesting to watch in particular how they give Gil's timeslipped period encounters a rich, dreamlike luster.

Shakespeare and Company — Ah, of course.

For whatever reasons of his own, this time Allen chose to concentrate his energies on crafting a light meringue, all air and sugar, not a main course weighted down with the usual meats and fats of Dysfunctional Human Dynamics and the Angsts of Existence. (Those are here too, but in eyedropper doses.)

Does Midnight in Paris work better because it is so lightweight, such candied ginger? I'll take the layers and nuances of an Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, or Stardust Memories any day, but, given Allen's output so far this century, he seems far more at home and assured with the ginger. It's an unexpected shift, but apparently a wise (or at least creatively strategic) one.

Also gone is the bitter anise that has for years been his films' dominant aftertaste. I still want to shake Allen by the shoulders and shout, "Yes, mortality sucks! Learn to cope with it!" At least this time he does in fact seem to be coping with it, or taking steps toward getting there, in his singular way. So now after the shoulder-shake I'd then take him to a club for Louis Armstrong's "Potato Head Blues" and propose a toast to having made it this far.

Its climax (such as it is) arrives when Gil announces his moment of clarity, and a facile Author's Message, by uttering "I'm having an epiphany. It's a minor one, but still." The moment struck me as Allen poking through the screen to acknowledge the wafer-thin mint he has whipped up here. If so, I'll take it over the gassy, charmless pork dishes he's offered over the past ten, twelve years.

I'll watch Midnight in Paris again, and my adding the eventual Blu-ray disc to the span of shelf space devoted to Allen movies is certain. That's a sentence I haven't been able to write in a long while, and it feels good to finally do so now. If it's the last time, ever ... yeah, I can accept that as a pleasant little dessert to go out on.

All the same, it feels good to actually look forward to his next film, The Bop Decameron, now shooting in Rome with Penélope Cruz, Alec Baldwin, Judy Davis, Ellen Page, Greta Gerwig, Jesse Eisenberg, and Roberto Benigni.

Gives me hope, it does. Maybe he'll go out with another masterpiece yet.

Via FilmDrunkDotCom on Vimeo and /Film.

* Nobody can do Woody's "Moose" bit as well as Jason Alexander, but mine would give him stiff competition.