However you classify it, it's certainly the best, hands down, science fiction movie Alec Guinness ever starred in.

What's that? B-b-but what about Star Wars?

Please. I'm as much a fan of those films as the next guy wearing a "Han Shot First" t-shirt. But the Star Wars movies are not science fiction as much as they're fantasy with rivets. X-wing fighters = magic flying carpets in gun-metal gray. Lightsabers? Prince Valiant's Singing Sword given a glow effect and cool vvvrrrrmmm sounds. And let's not even start with the Force.

No, in this case I'm applying the Asimovian definition of science fiction as a tale that unveils human passions and foibles via a technological advance. Under those (admittedly strict) terms, The Man in the White Suit is pure science fiction, a story that would be right at home within decades' worth of Analog or Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine. At the same time it's one of the slyest of comedies from London's Ealing Studios, where Guinness permanently stamped his place in movie history with Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (also '51), and The Ladykillers (1955).

No, in this case I'm applying the Asimovian definition of science fiction as a tale that unveils human passions and foibles via a technological advance. Under those (admittedly strict) terms, The Man in the White Suit is pure science fiction, a story that would be right at home within decades' worth of Analog or Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine. At the same time it's one of the slyest of comedies from London's Ealing Studios, where Guinness permanently stamped his place in movie history with Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (also '51), and The Ladykillers (1955).(Check out WFMU radio's "epic nerd-off" Science Fiction Trivia Challenge between John Hodgman and Patton Oswalt to hear the participants riff on how Guinness' long and august career was eclipsed by Star Wars mania. Oswalt's "Lavendar Hill-con" endears him to me forever. It starts at the 15:03 mark.)

While on the surface it's a comic fable with a sense of humor as dry as a cracker, The Man in the White Suit possesses a sharp edge that rises like a shark fin above the natty British drollery. The theme of the Establishment vs. the "common man" was practically a British genre of its own, and like Peter Sellers' breakthrough film, I'm All Right Jack ('59), here's a damning satire of British Establishment conservatism, industrial capitalists, and trade unions, one that strives to be both funny and dour, and succeeds at both — an achievement postwar Brits so excelled at.

So here's a superb tea-and-biscuits take on the Prometheus myth. The setting is transferred to the smokestacked landscape of industrial Manchester, and naive boffin Sidney Stratton is the bringer of wonders who must pay a price for his unrepentant actions.

At its center is a lovely performance from Guinness as the tweedy Stratton, an impassioned obsessive whose invention could provide incalculable benefits to all humanity, therefore he and it must be stopped at all costs. He takes menial jobs in textile mills so that he can sneak time in their labs to work on his secret experiment — a bubbling, oomp-pahing contraption of mysterious purpose. Although a brilliant Cambridge honors grad, Stratton is blinkered by his single-mindedness (these days he'd likely be labeled with Asperger's), and the forged expenses incurred by his experiments repeatedly get him sacked, mill after mill.

But at last he scams his way into the laboratory of his dreams, and after a series of literally explosive experiments, his "Eureka!" moment arrives with the discovery of a revolutionary new fiber that is indestructible and repels dirt and stains.

But at last he scams his way into the laboratory of his dreams, and after a series of literally explosive experiments, his "Eureka!" moment arrives with the discovery of a revolutionary new fiber that is indestructible and repels dirt and stains.The factory owner (Cecil Parker) sees the miracle fabric as the ultimate boon for his company, and in short order a tailor whips up a demonstration suit for Stratton. The resulting luminous white trousers and jacket not only glow even in the dingy daylight, they give Stratton the air of an ultramodern White Knight tilting at one mission in life: to free mankind from washtime drudgery and the indignities of tattered clothing.

Naturally, the monopolistic textile industry leaders, led by a seemingly mummified tycoon (Ernest Thesiger as a Monty Burns prototype), see only a threat to their well-fed status quo. Their attempts to coerce Stratton and suppress his discovery include money (he blinks befuddled at £250,000), deception, incarceration, and even sex. They employ his boss' sexy daughter Daphne (yummy, plummy-voiced Joan Greenwood) to seduce him, but his steadfast nature and unblemished idealism turn her sympathies toward Stratton ("flotsam floating on the floodtide of profit," she says of him) and against the cold self-preservation of papa or her would-be Establishment suitor, Michael Gough.

(Pardon me a moment while I imagine Joan Greenwood breathing softly into my ear with that voice like warm butterscotch pudding.... )

On the other side of the capitalist coin, the local textile workers union see only an end to their livelihoods. Their point of view is poignantly hammered home by Stratton's frail old landlady (Edie Martin), who makes ends meet with laundry services and who asks her on-the-lam tenant, "Why can't you scientists leave things alone? What about my bit of washing when there's no washing to do?"

In the most unified of Luddite Rebellions, both Capital and Labour join forces and, like Frankenstein's villagers with torches, set out into the streets to capture Stratton and prevent the publication of his discovery.

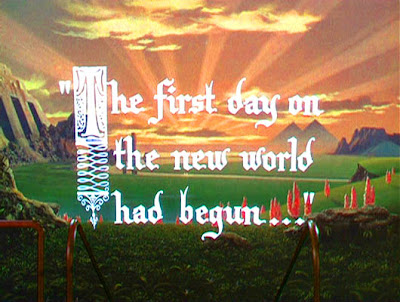

In the most unified of Luddite Rebellions, both Capital and Labour join forces and, like Frankenstein's villagers with torches, set out into the streets to capture Stratton and prevent the publication of his discovery.The climax strikes a stark note — Stratton standing symbolically naked before the desperate mob — followed by a somber yet uplifting coda: Stratton, single-minded as ever, exits the picture walking away on a lonely street, his head held high, looking for all the world like Chaplin's Little Tramp on the road toward an ambiguously hopeful future.

Chaplin isn't the only classic comedy icon that comes to mind through The Man in the White Suit. With his straight-faced determination and the film's precision-tuned physical humor, Guinness' Sidney Stratton could be one of Buster Keaton's resolute can-do amateurs facing down unexpected forces he scarcely comprehends.

American-born director Alexander Mackendrick (The Ladykillers) oversaw it all with laudable restraint. In a dozen ways this Oscar-nominated screenplay could have become a diatribe, its "message" either shrill or mean-spirited, but Mackendrick avoided every pitfall. He juggled tension or tenderness with humor that's dry and funny without being stuffy. Although the characters are quickly drawn, they're also touching or sympathetic without caricature, condescension, or sentimentality.

American-born director Alexander Mackendrick (The Ladykillers) oversaw it all with laudable restraint. In a dozen ways this Oscar-nominated screenplay could have become a diatribe, its "message" either shrill or mean-spirited, but Mackendrick avoided every pitfall. He juggled tension or tenderness with humor that's dry and funny without being stuffy. Although the characters are quickly drawn, they're also touching or sympathetic without caricature, condescension, or sentimentality.The Man in the White Suit sure has aged well. No doubt many modern viewers can point to ways in which its concerns and sensibilities are even more "true" over a half-century later. Its acerbic and observant stabs at industry and the darker side of self-protecting capitalism remain clothesline fresh today.

In the end, the indestructible suit's representation of Progress and "the welfare of the community" may be no match against the panicky vested interests of the powerholders and the everyday blokes who simply want to keep their jobs. Nonetheless, what perseveres even in the face of failure is the dignified, forward-looking spirit of discovery and enterprise personified by Sidney Stratton, a fabric impervious to the narrow interests of both Left and Right.

Science fiction as social or topical commentary has a significantly more potent history in novels rather than films. Still, 1936's Things to Come (scripted by H.G. Wells) is an early example (granted, its message-making was as subtle as a punch in the face from Mr. Wells himself), and even the factory sequence in Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times (also '36) provides an unmissable metaphor for dehumanization via industrialization.

Other examples range from A Clockwork Orange (youth violence/state-imposed social conformity), Soylent Green (environmentalism), and The Stepford Wives (backlash against the Women's Movement), to recent titles such as Minority Report, V for Vendetta, Children of Men, and District 9. Satirical science fiction film comedies are even rarer, although Dr. Strangelove sure raised that bar to a still-unbeaten level.

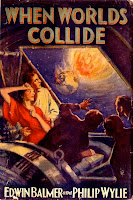

I agree that The Man in the White Suit is an outlier among that obviously science-fictiony group. It's science fiction "lite," and I'll bet that no one involved with its production would have considered it "science fiction" at all. However, looking at it now there's no question that it's intelligent, funny, splendidly acted and directed, and one of the sharpest comedies to stand the test of time — and a movie that science fiction should be proud to call its own from the same year as The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Thing from Another World, and When Worlds Collide.

Music: Susannah McCorkle, "The Waters of March"

Near at hand: Memo on yellow Post-It, "dog sitter for Kai"