In a couple of weeks Elizabeth and I will be in London. The circumstances behind the trip caught us by surprise. We weren't planning to go to London until, well, things happened and suddenly we had tickets on British Air. (Portland, New York, and San Francisco are now also on our pleasure/business calendar between now and November. Elizabeth is jetting off to L.A. tomorrow evening. It's a whirlwind, I tell you.)

In a couple of weeks Elizabeth and I will be in London. The circumstances behind the trip caught us by surprise. We weren't planning to go to London until, well, things happened and suddenly we had tickets on British Air. (Portland, New York, and San Francisco are now also on our pleasure/business calendar between now and November. Elizabeth is jetting off to L.A. tomorrow evening. It's a whirlwind, I tell you.)As I mentioned here, on our itinerary is the current production of Dr. Faustus at Shakespeare's Globe. Of course, me being the guy I am, that guaranteed that I'd reach to the DVD shelves to pull out another British take on the Faust legend: Bedazzled from 1967. This cheeky comedy infused the centuries-old story with the spirit of Swinging London plus impudent pokes at religion, politics, and pop culture itself.

Any conversation about the so-called British Invasion of the 1960s tends to focus on the new pop and rock music that tsunamied over American popular culture mid-decade. But riding that wave also came new styles of envelope-pushing comedy.

This brash, cocksure postwar generation of young Oxbridge-educated comics modernized the British tradition of satire with sharp verbal wit, straight-faced or absurdist approaches to outrageous material, and gimlet-eyed sarcasm toward the previous generation's institutions. Political figures, religion, the upper classes, "high" and "low" culture/society/art — all were now open targets for unapologetic lampooning.

In the early '60s, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, with Jonathan Miller and Alan Bennett, led this New Wave satire movement in Beyond the Fringe, a stage revue that began at the Edinburgh Festival and then went on to acclaim in London and on Broadway. Cook and Moore furthered their comedy partnership — "Pete and Dud" — on British television, most notably in their hit BBC series Not Only...But Also.

With this success in their pockets, they pitched a film to Twentieth Century Fox, a mod spin on the Faust legend, with Moore as the woebegon schmuck who sells his soul to Peter Cook's dry, wry horned one.

As luck would have it, they already had an enthusiastic fan in director Stanley Donen, whose creds included Charade and Two for the Road, as well as top-drawer movie musicals in the 1950s: On the Town, Funny Face, and Singin' in the Rain. Donen asked to work with Cook and Moore, and in 1967 — the year of Sgt. Pepper and The Who smashing their kit at Monterey — the duo's best film, Bedazzled, opened their distinctive brand of humor to new audiences, with hopes toward going really big in the huge new U.S. market.

As timid, tongue-tied Wimpy's short-order cook Stanley Moon (a role that leaves me aching that he never co-starred with Rowan Atkinson), Moore pines for an aloof waitress, Margaret Spencer, played by veteran comic actor Eleanor Bron. So unrequited is his love and so deep his anguish that this hapless hash-slinger opts to hang himself from his tiny flat's water pipe. His goodbye note leaves Margaret his collection of moths.

He fails at that too, of course, although he does attract the attention of Mr. George Spiggot (Cook), a dapper swell who knows more about Stanley than anyone else cares to. Spiggot reveals himself to be none other than the Unholy One, evil incarnate himself.

Stanley: "I thought you were called Lucifer."

George: "I know. 'The Bringer of the Light' it used to be. Sounded a bit poofy to me."

It turns out that rather than sitting on a throne of skulls in his fiery infernal kingdom, the devil makes his God-appointed, workaday living as the proprietor of a grubby London nightclub and business office staffed by the Seven Deadly Sins. "What terrible sins I have working for me," he says of the riffraff Anger, Sloth, etc. "I suppose it's the wages."

He offers Stanley seven wishes in exchange for the miserable little soul that, he says, is no more useful than Stanley's appendix. The appeal is irresistible to desperate Stanley: a chance to remake himself in any way imaginable to win Margaret's heart (as well as, naturally, her other bits).

Thus begins, with the magic incantation "Julie Andrews!", an episodic series of altered-reality shaggy-god scenarios that place Stanley in situations of his choosing — as an intellectual aesthete, a millionaire already married to "highly physical" Margaret, a pop star with Margaret among the hoard of groupies, a fly on the wall (endearingly cartooned), and so on.

The Devil, though, can't resist the opportunities to insert himself into Stanley's wishes and screw them up. After all, it's in his job description. It's the old "Be careful what you wish for" angle, with the wording of Stanley's wishes interpreted with all the fiendish legal exactitude of an iTunes Terms & Conditions form.

Cook's deadpan skewering of fleeting pop-idol vanities will never lose its currency. "I'm callous … I'm dull … You bore me ... You fill me with inertia," he monotones as Drimble Wedge & the Vegetations, upstaging and out-groupie-ing Moore's Tom Jones–esque soul-cry, "Love Me!"

The silliest/funniest sequence arrives when exasperated Stanley wishes to be with Margaret in a place of peace and spiritual purity: there he and Margaret find love as nuns in the cloistered Order of the Leaping Berylians, whose rituals require their sacred trampolines. (This bit originated with a sketch on Pete and Dud's Not Only...But Also.)

To exit a fantasy, all Stanley has to do is blow a raspberry (a fitting response to worldly inadequacies, I think), whereupon he returns to wherever George happens to be awaiting the next attempt.

But the best of the many funny moments here aren't necessarily Stanley's fantasy sequences, which sometimes drag. They're the in-between bits with Moore and Cook in their well-honed dialogue mode.

In their chats about theology, morality, organized religion, and the nature of evil, Stanley learns that old Beelzebub is just another put-upon civil servant following orders. He may be the Prince of Darkness, but Spiggot's 24/7 job is chiefly urbane sarcasms and petty pranks such as expiring the time on parking meters, scratching LP records, melting ice lollies, gouging "ventilation" holes in oil tankers, targeting pigeons' bombardier runs, and phoning Mrs. Fitch ("Abercrombie here, I work with your husband") to tell her that Mr. Fitch has just checked into the Cheeseborough Hotel Brighton with his secretary.

It's a mundane, dreary job for God's favorite fallen angel who aspires only to earn his way back into Heaven now that mankind can do his work well enough without him. So naturally he's suffering from burn-out and a lack of that driving inspirational spark:

"There was a time when I used to get lots of ideas. I thought up the Seven Deadly Sins in one afternoon. The only thing I've come up with recently is advertising."

Honestly, who among us can't identify with him? Stanley tells Margaret that although George is the Devil, "he's not so bad once you get to know his problems." Meanwhile, George shows signs of affection for the sad-sack little twerp, and together the pair form, however temporarily, a convivial mutual-support rapport.

Honestly, who among us can't identify with him? Stanley tells Margaret that although George is the Devil, "he's not so bad once you get to know his problems." Meanwhile, George shows signs of affection for the sad-sack little twerp, and together the pair form, however temporarily, a convivial mutual-support rapport. Bedazzled stitches its sketch-comedy scenes together with winning banter and collegiate theological spoofery: Mussolini barely slipped through George's grasp ("all that work, then right at the end with his last breath he says, 'Scusi, mille regretti,' and up he goes!"), God is English and "very upper class," the Garden of Eden was "a boggy swamp just south of Croydon; you can see it over there."

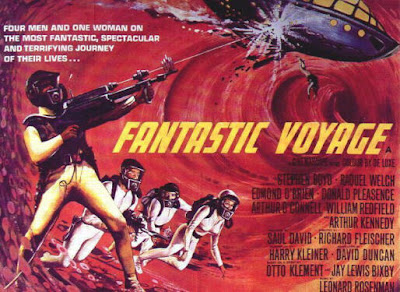

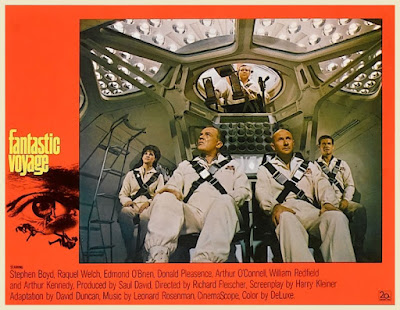

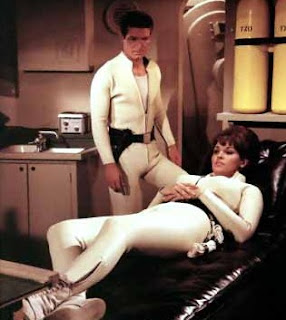

Squeezably sexy Raquel Welch, clad in Frederick's of the Underworld lingerie, steals her scene as Lust, an American Southern hothouse flower, in a bedroom cameo/typecasting. The promo imagery, from the film's original advertising (e.g., the posters at the top and bottom of this page) to the current DVD box art, oversells her brief presence, but it's an understandable marketing ploy from her peak pinup years between One Million Years B.C., Fantastic Voyage, and The Magic Christian. Cook had suggested titling their film Raquel Welch so the posters could read "Peter Cook and Dudley Moore in Raquel Welch." Oddly, that didn't fly.

And that's Barry Humphries ("Dame Edna Everage") appearing as Envy.

The old sporting rivalry between George and God dates back at least to Job (who, George says, "was what you'd technically describe as a loony)." But a game of equals it isn't. Eons ago God may be have challenged George to a round of metaphysical chess, then provided him with little more than a Snakes and Ladders board, giggling behind His hand while fucking with earnest George.

It's no spoiler to note that due to a technicality in the contract Stanley gets to keep his soul. Still, George makes sure that he gets in the last word:

[to God] "All right, you great git, you've asked for it. I'll cover the world in Tastee-Freez and Wimpy Burgers. I'll fill it with concrete runways, motorways, aircraft, television, automobiles, advertising, plastic flowers, frozen food and supersonic bangs. I'll make it so noisy and disgusting that even you'll be ashamed of yourself! No wonder you've so few friends; you're unbelievable!"

Looking around at the state of things over the intervening 44 years, especially now with a U.S. election cycle revving up with its new class of crackpot evangelical politicos who've signed their own regrettable contracts with George, we can only admire George for being so thorough at his underpaid, tedious job.

Looking around at the state of things over the intervening 44 years, especially now with a U.S. election cycle revving up with its new class of crackpot evangelical politicos who've signed their own regrettable contracts with George, we can only admire George for being so thorough at his underpaid, tedious job.All the same, the fade-out makes it clear that it's God, as usual, who has the last belly laugh. It's good to know the "great git" still has a wicked sense of humor.

On the down side, after a while the film doesn't quite generate the energy needed to sustain its momentum. The narrative doesn't so much "arc" as stretch out as straight as a block of sidewalk slabs. Each slab is funny to its degree, though occasionally we're ready to move on to the next one before it's ready to let us go.

Bedazzled is bedeviled by what appears to be a directorial ambivalence, or a creative arrow that lands a couple rings off the bull's eye. Old-school Donen directed with an eye toward modish stylings. As a result we view much of Bedazzled through the murk of soft focus or on-set filters. He's Stanley Donen, so he knows how to fill a screen well, but there's no question that Welch is all but wasted when viewed through filmy bedcurtains. And that's not to mention the flare of stage lights projected straight into the camera. Now, director of photography Austin Dempster may shoulder the lion's share of this. His IMDb profile lists Bedazzled as his first promotion to DP after years (since 1941) as a "camera operator" and the occasional second-unit photographer.

Either way, Donen seems too timid to fully unfurl his New Wave freak flag, alternately shooting Moore and Cook straight up without augmenting their established dialogue-heavy partnership. That's all to the good verbally although I still see the pair straining against the 35mm frame surrounding them.

I wonder if the Donen of Charade and Arabesque was too restrained, too generationally inhibited to really make the most of his two leads. Richard Lester might have been a better fit. I can imagine the director A Hard Day's Night, The Knack, and Petulia adding his own contemporary backspin that allowed Cook and Moore to send the material into orbit with the riffing spontaneity of their stage and British TV work. Donen's other film from '67, the British comedy Two for the Road (also with Bron), feels more comfortable with its "experimental" side, in that case a fractured-time narrative structure reminiscent of Lester's Petulia. (Lester did direct Cook and Moore two years later in the post-apocalyptic farce The Bed-Sitting Room.)

Nonetheless, Bedazzled supports itself amiably on the heads of its two stars. Besides carrying the lead roles, Cook wrote the screenplay and Moore crafted the score, which he performed with his jazz trio.

The film didn't make the hoped-for splash in the States, so any potential Pete-and-Dud wave over here never rose above a ripple. It opened in '67 on December 10, the same month that also saw the release of The Graduate, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, and Valley of the Dolls, numbers 2, 4, and 6 of the top-grossing films that year. So it's not a big leap to suggest that such a comparatively small film got lost in the Klieg lights of the unarguably greater titles around it.

The film didn't make the hoped-for splash in the States, so any potential Pete-and-Dud wave over here never rose above a ripple. It opened in '67 on December 10, the same month that also saw the release of The Graduate, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, and Valley of the Dolls, numbers 2, 4, and 6 of the top-grossing films that year. So it's not a big leap to suggest that such a comparatively small film got lost in the Klieg lights of the unarguably greater titles around it. Bedazzled did mark a turning point in the career trajectories of Cook and Moore. By all accounts Cook was the more productive and inventive writer-comedian of the two, and was handily the lead dog in the pack in the U.K., with Moore at ease as Cook's natural second banana. But Cook the anti-establishment satirist's dry, acerbic, erudite wit and absurdist approach to comedy didn't catch fire in the U.S. He was a transformative influence on comedians that came after him both in the U.K. and the U.S., and even this long after his death in 1995 there's no denying an ongoing legacy in the shape and form comedy has taken since his active years. (In 1999 the main-belt asteroid 20468 Petercook was named after him, so there's some more posterity for you.) He was a gifted groundbreaking comic that simply didn't translate well to a broader medium.

On the other hand, "Cuddly Dudley" came across as more likeable and identifiable, more agreeably mainstream. After more years in a few subpar British films — including a terrible comic interpretation of The Hound of the Baskervilles as Watson to Cook's Sherlock Holmes — Moore's post-Bedazzled career eventually spun up to a house in Malibu and Hollywood hits such as 10 (1979) and Arthur (1981). While both actors bounced between London and L.A. into the '80s, only Moore achieved household-name status in the U.S.

They remained close after the break-up of their long partnership, and reunited by performing on stage together at benefits such as Comic Relief for the homeless in the U.S. and The Secret Policeman's Balls for Amnesty International in the U.K.

|

| Japanese poster |

The few vintage extras on the DVD are welcome even if they're not substantial. In an amusing off-the-cuff promo, "Peter and Dud: Interview with the Devil," filmed on-set. Moore appears as a TV interviewer collaring George Spiggot, Esq., a.k.a the Devil. A five-minute clip gives us Cook and Moore discussing their shared history on L.A.'s "Paul Ryan Show" in 1979 when Moore was just about to hit stardom in Blake Edwards' 10.

Finally, a newer piece is a six-minute interview with Harold Ramis, director of the 2000 remake starring Elizabeth Hurley and Brendan Fraser, lauding the original. Also here are the American trailer and a click-through image gallery of 20 behind-the-scenes stills.

Music: Betty Carter

Near at hand: sandals off