Then again, already this summer we had those strange few weeks in the news, something about deep-cover Russian spies out to make big trouble for Moose and Squirrel in suburban humdrum America. Of course, the news cycle boosted the made-for-reality-TV cuteness of Anna Chapman (rather, "Anna Chapman"), who's now back in Mother Russia where her Clairol Girl features accompanied her inherent ugliness in a hero's welcome. Still, if Firefly/Serenity's Jewel Staite plays her in the inevitable TV movie, maybe a greater international good has been served.

Meanwhile, the self-replicating crazy-makers drill their wells even deeper by telling us that foreign Islamist terrorists are sneaking into Real America by collaborating with Mexican drug cartels, as if we're being urged to imagine Blofeld and SPECTRE teaming up with Al Pacino's Tony Montana, probably with a bit of Grand Theft Auto thrown in for extra excitement.

And jeez, Edith, we just watched, eyes rolling, the Breitbart-Sherrod controversy. Because the universe has a keen sense of irony, that little imbroglio arrived gasoline-hosed by the Fox News Birth(ers) of a Nation Power Hour during recognition of To Kill a Mockingbird's 50th anniversary. Plus, hordes of invading American Muslims, like dirty Commies in the days of yore, apparently need to be refudiated here in the land of the free. Oh, and look — it's becoming clear that Vietnam more and more shares a big, porous border with Afghanistan (see History, doomed to repeat it).

And jeez, Edith, we just watched, eyes rolling, the Breitbart-Sherrod controversy. Because the universe has a keen sense of irony, that little imbroglio arrived gasoline-hosed by the Fox News Birth(ers) of a Nation Power Hour during recognition of To Kill a Mockingbird's 50th anniversary. Plus, hordes of invading American Muslims, like dirty Commies in the days of yore, apparently need to be refudiated here in the land of the free. Oh, and look — it's becoming clear that Vietnam more and more shares a big, porous border with Afghanistan (see History, doomed to repeat it).I wonder: Will the big take-away from the year 2010 be how often we've looked back to the 1960s and sighed heavily? The times they are rewindin'? Perhaps we can find comfort in the apostle Paul, who was there too and once wrote:

Paranoia strikes deep in the heartland,These are, as Shakespeare might put it, tragical-comical-historical times, and you can decide for yourself what order those words should come in.

But I think it's all overdone.

Exaggerating this and exaggerating that,

They don't have no fun.

It can be instructive, or at least perspective-adjusting, or maybe just amusing, to let movies take us back in time a few decades to see that the more things change, the more some people, well, not so much. (Yeah, I know: I similarly hobbyhorsed Mockingbird and Blazing Saddles recently too. I'm like a dog with a bone that way.)

This is one I caught on Sunday afternoon TV quite often as a '70s kid, and even then I knew I was watching something from some vague "before" time. Still, I remember finding it humorous and fun. Every time I see Alan Arkin in anything, which isn't often enough these days, I flash back to enjoying him first here in the role that made the erstwhile Second City alum and Broadway actor a movie star. Indeed, Arkin, as the hapless lieutenant charged with getting his beached crewmates back home safe and sound — and spouting authentic Russian learned for the film — is worth the viewing all by himself. And back then, with my nascent critical eye, I could tell that this was a well-made piece of funny business; at least in my memories it has maintained a good-looking, A-list production gloss.

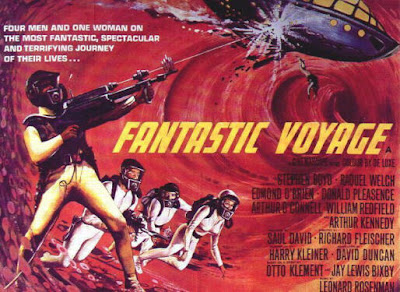

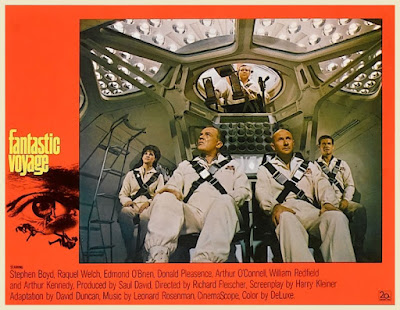

But does it hold up today, 44 years later? Like two others from 1966 I've written about here, Our Man Flint and Fantastic Voyage, the answer is a qualified yes, though this one — in its spoofing of stepping-on-rakes paranoia and "there be foreigners!" saber-rattling — is more tuned to the phobias of our times.

After a Soviet submarine runs aground near a Norman Rockwell New England coastal village, nine sailors (led by Arkin) venture ashore ("we are of course Norwegians") to quietly borrow a motor boat for a tug back to sea.

Naturally, it isn't long before misunderstandings on both sides escalate the incident and the "Russian invasion" boils over to potential cataclysm.

The running hither-and-thither townspeople include a vacationing New York writer (Carl Reiner in the longest sustained Jimmy Stewart impression on record) and his wife Eva Marie Saint. Young Sheldon Collins plays their son Pete as the same trigger-happy little shit be played in the following year's The President's Analyst.

Giving the film a balancing world-weary deadpan is Brian Keith as the straight-faced police chief. His placid existence receives an unwelcome kick from Paul Ford (The Music Man) as the VFW hawk out to secure the borders and defeat the invading Red legions. Assisting him is Jonathan Winters as, pretty much, Jonathan Winters. Theodore Bikel appears briefly as the Russian captain.

And it wouldn't be Hollywood without a syrupy romance between the Pretty American Girl (Andrea Dromm) and the Handsome Good-Hearted Russian Lad (John Phillip Law), with both actors making their Hollywood debuts.

And it wouldn't be Hollywood without a syrupy romance between the Pretty American Girl (Andrea Dromm) and the Handsome Good-Hearted Russian Lad (John Phillip Law), with both actors making their Hollywood debuts.Comely, sunny-haired Dromm caught my attention back in the day, looking for all the world like a Beach Boys song given form and flesh. I knew her best from TV reruns of her other 1966 role: "Yeoman Smith" in the second pilot episode of Star Trek. She spoke only one line ("The name's Smith, sir"), but she looked mighty cute there on the Enterprise bridge. I've read that Dromm was offered a choice between an ongoing role in the still-unproven TV series and a lead part in this big Hollywood movie. Choosing the movie was the obvious best move at the time, though she has said that if she'd known what an enduring hit Star Trek would become, she might have chosen differently. As it is, you probably don't have to Google hard to find Yeoman Smith fanfic steaming up pixels somewhere.

At 6'5" with a blue-eyed boyishness, it's only natural that Law went on to become a mid-list movie and TV sex symbol. Genre-film cognoscenti salute his presence in Mario Bava's Danger: Diabolik! ('68), as the blind guardian angel Pygar kinking it up with Jane Fonda in Barbarella (also '68), as Snoopy's arch nemesis the Red Baron in Roger Corman's Von Richtofen and Brown ('70), and as the stout-hearted sailor-adventurer confronting nifty Ray Harryhausen creations in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad ('73).

Their romance is the vessel from which the movie's Make Love, Not War oils are poured, as in the sugary charm of their Capulet-Montague seaside dialogue:

Alexei: "In Union of Soviet, when I am only young boy, many are saying, Americanski are bad people, they will attack Russia. So all mistrust American. But I think that I do not mistrust American... not really sinceriously. I wish not to hate... anybody! [He chucks a stone into the sea] This make good reason to you, Alison Palmer?"

Alison: "Well, of course it does. It doesn't make sense to hate people. It's such a waste of time."

The even-handed script parades no simplistic evil empires or Old Glory platitudes. Instead it mines the nervousness and paranoia on both sides, and the climax comes with townsfolk and submariners literally staring down each other's gun barrels — a tidy little metaphor for the Cold War. The crisis' contrived resolution may leave you either wiping a tear or rolling your eyes (as if those are mutually exclusive), with World War III narrowly averted by good ol' hands-across-the-water pluck.

Pub Trivia Contest points: Rose based his screenplay on a 1961 novel, The Off-Islanders, written by Nathaniel Benchley. Later, Nathaniel's son Peter found his own way in life by writing the novel Jaws, which Steven Spielberg turned into another little look-what-showed-up-on-the-beach movie you might have heard of.

It's easy to see why The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming was welcomed as a warm and affirming counterpoint to its darker cinematic cousins such as Fail-Safe. It skewers hawkish reactionism and mob militancy, and its sympathetic portrayal of the beached Russians — not to mention the panicky buffoonery of the Americans — probably gave the more rabid Commie-haters conniptions.

It was popular in its day and praised by contemporary critics, with Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Best Actor in a Leading Role (Arkin), Editing (future director Hal Ashby), and Adapted Screenplay. It won the Golden Globes for Best Musical/Comedy and Best Actor (Arkin), with noms for Best Screenplay and Most Promising Newcomer (both Arkin and Law).

Although it's frozen in amber now, it remains an amusing (if dated and overlong) slice of the 1960s. To Boomers above a certain age it's a fondly remembered piece of fluffy nostalgia. For everyone else it's an entertaining-enough time portal to another epoch. DVD film-fest this one with Fail-Safe and Dr. Strangelove for a snapshot of how a previous generation's fears played out in popular culture.

In 44 years, what comedies will they be making about us and our time? I have some ideas....

Music: The Red Elvises, "Tchaikovsky"

Near at hand: An origami globe built from intersecting Hearts suit playing cards.