A few days ago, while in San Francisco, I received some pleasant email regarding a piece I wrote years ago about the George Pal interpretation of H.G. Wells' The Time Machine. As happenstance would have it, for a while I've been this close (imagine my thumb and fingertip measuring the depth of Uwe Boll's chance of an Oscar) to adding a post here on that same topic; I just never got around to it. Now back from SF and spurred on by the nice email, I figure it's time to get to it. I'm aiming to post it later this week. (And here it is.)

A few days ago, while in San Francisco, I received some pleasant email regarding a piece I wrote years ago about the George Pal interpretation of H.G. Wells' The Time Machine. As happenstance would have it, for a while I've been this close (imagine my thumb and fingertip measuring the depth of Uwe Boll's chance of an Oscar) to adding a post here on that same topic; I just never got around to it. Now back from SF and spurred on by the nice email, I figure it's time to get to it. I'm aiming to post it later this week. (And here it is.)First, though, I want to ramp up to The Time Machine by addressing an earlier film I've referenced in three previous posts (those on The Man in the White Suit, Modern Times, and The War of the Worlds). It's 1936's Things to Come, produced from a screenplay written by Wells himself. Let's finally open the tap and take a big gulp from this one.

If you were an adult in the movie-going audience in the 1930s, it's a safe bet that you remembered, one way or another, the unprecedented horrors of the World War roughly 15 years earlier. The "war to end war," people called it, a phrase popularized by H.G. Wells in 1918, though he noted (in In the Fourth Year) that as a catch-phrase it had "got into circulation" by the end of 1914. And yet by the mid-thirties throughout England and continental Europe, the grinding Great Depression and Hitler's rhetoric were quite plainly setting the table for a Second World War.

To a disgruntled yet cautiously optimistic H.G. Wells, only scientific reason — not religion or capitalism — could be Mankind's savior in that most desperate hour, could give us the tools to finally rise above our baser animal selves and reach nobly toward a future built on peace, prosperity, progress, and the enlightened road of evolved socialism.

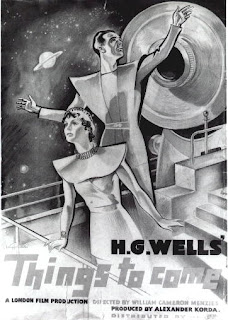

His best works (such as The Time Machine) long behind him and, at nearly 70, a waning Grand Old Man of literary highbrows, Wells collaborated with producer Alexander Korda to communicate his worldview on an epic scale. Together they adapted Wells' strange 1933 manifesto, The Shape of Things to Come, into a movie that was to serve as a cautionary tale, an anti-war plea, and a grandly self-confident platform where Wells' beliefs and fears could be realized and understood by worldwide audiences.

The result, the visually spectacular but arid and tendentious Things to Come, holds an important place in the history of science fiction cinema. As a visionary work that aims to honestly tackle the devastating consequences of international warfare, this is one of the few science fiction films that's about something, that's meant to offer you mental popcorn to munch on long after the "The End" card.

The movie "predicts" desktop video screens and big-screen TV, evil despots with an eye toward misusing the beneficent fruits of super-science, and a world knitted together by technologies such as long-distance communications and easy air travel. The May '36 issue of Modern Mechanix & Inventions, in a six-page spread on the film's "amazing achievements predicted for the world of tomorrow" (reproduced in full here), opined that in Things to Come...

...we have painted for us an astonishing picture in which there is not a single development which does not follow naturally out of laboratory discoveries of our own day. It is inspiring for us folk of 1936 to realize that the progress of science, as presented each month in the pages of Modern Mechanix & Inventions, is laying the foundation for a new civilization.

For his director, Korda hired an American scenic designer, William Cameron Menzies. Although he had won the first Academy Award for production design, this was the first time Menzies had been tasked with directing a feature-length project on his own. His work as production designer and sometimes-director can be seen in visual spectacles such as the Raoul Walsh/Douglas Fairbanks Thief of Baghdad (1924), Korda's 1940 Thief of Baghdad, the original Invaders from Mars, and most memorably Gone with the Wind. Korda also hired a young Jack Cardiff, soon to become one of the most innovative and lauded cinematographers, as special effects camera operator.

Things to Come is a product of its time and place and writer. That's important to understand if we're to appreciate it as something more than a creaky black-and-white polemic dressed up in flaring shelf collars. Even so, in its day it was a box-office flop. After Things to Come premiered, Wells' heart must have sunk as audiences avoided his philosophically impassioned and idealistic — yet dour and didactic — cri de coeur. Created to stimulate the intellect more than the emotions, the movie is preachy, slow-paced, and oh so upper-class English. Menzies, aided by art director Vincent Korda, filled the screen with awe-arousing visuals from the purest heady dreams of the Gernsback continuum, but his stiff and dry directing gave more personality and dimension to his sets than to his actors.

Moreover, Wells had no prior experience writing for film, and his screenplay exhibits few cinematic, or even dramatic, instincts. (Even after two prior versions: the first, titled Whither Mankind?, was utterly unusable; the second unfilmable but several steps closer to a workable script.* Everyone onscreen has a speech to make, and sometimes the speech-making is used the way Robert De Niro uses a baseball bat in The Untouchables. Philosophically the film's agenda is blinkered and naive (but audaciously so), and Wells' good intentions are undercut when the script takes its own moral probity as self-evident truth, which often translates as smugness or gormlessness.

Add the declamatory acting and the "futuristic" costumes that look like a WPA production of Oedipus Rex, and we have a movie that began aging badly on its opening day.

Things to Come opens with a near-future forecast of Christmas 1940 in the metropolis of Everytown (obviously London), a city threatened by world war. Pacifist intellectuals, such as John Cabal (Massey), try to turn the tide.

But Cabal's efforts go unheeded by the self-interested classes, and war arrives with tanks and aeroplanes and gas bombs. Everytown is destroyed by air raids (dramatically enacted four years before the real thing). The war continues for thirty years, thought by the end its original purpose is long forgotten.

As a result, civilization degenerates while "the Wandering Sickness" and devastation accelerate the spiral down until 1970, when the world has crumbled into a balkanized Mad Max Dark Ages. Everytown is ruled by a barbaric warlord, the Boss (Ralph Richardson), as the war continues on a Medieval scale throughout the Pestilence Years.

The Boss (the most anti-intellectual nationalistic neoconservative authoritarian blowhard to never receive a Fox News paycheck) desperately wishes for technological superiority over his enemies, especially via air travel, but everyone knows that no such technology exists anymore.

Nonetheless, some scientists, such as Doctor Harding (Maurice Braddell) and the mechanic Richard Gordon (Derrick De Marney), refuse to believe that civilization can't still be saved through technology. Sure enough, a strange craft appears among the clouds. The Airman emerges: John Cabal, 30 years older but still looking sharp as the deus ex machina in a black rubber flightsuit and enormous bubble helmet.

He represents Wings Over the World, an enlightened society of scientists and engineers, and is scouting the land to assess the savage tribal communities that have replaced civilization. Cabal promises the people a new, superior civilization "of law and sanity" that needs no Bosses or independent sovereign states, but only if the people put their faith in Science rather than in the Boss and his kind.

Naturally, the Boss wants to prevent Cabal from taking away his power. He imprisons the Airman while he battles a neighboring tribe. The Boss' female companion, Roxana (Margaretta Scott) — apparently the only truly interesting woman in a hundred years — is intrigued by the freedom and intellectual curiosity that Cabal represents. With her aid, Cabal helps Gordon escape with a flying machine to World Communications (a "government of common sense"), where Gordon informs the technocratic elite of what has happened to Cabal in Everytown.

Soon mammoth flying fortresses appear over Everytown, defeat the Boss' forces, and drop Peace Gas which knocks out the populace. Cabal declares that the Boss is "dead, and his world dead with him." The people of Everytown awaken to the birth of a new planned society of reason.

In an impressive sequence, we witness the next 70 years pass in a montage as Mankind's immense machines rebuild the world phoenix-like from the ashes of primal ruination.

Finally, we reach 2036. Behold the new, improved Everytown — an enormous art deco Brave New World, an enclosed subterranean Raygun Gothic supercity as gleaming white as a Sunday school ideal of Heaven. A little girl receives a history lesson by her grandfather, and she expresses delight that people will "keep on inventing things and making life lovelier and lovelier." (I'm not against the sentiment at all, although a more irksome use of a child as a mouthpiece for the author won't happen again until Charlie Chaplin's A King in New York in 1957.) Every aspect of human life (except apparently the fashion industry) has never been better, thanks to Science.

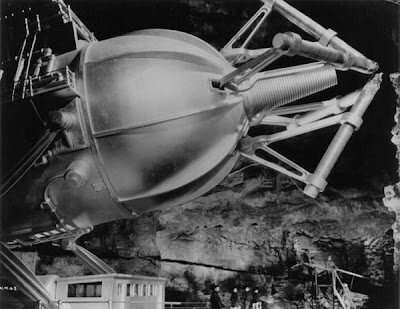

However, not all is well. A sculptor, Theotocopulos (Cedric Hardwicke), represents reactionary artists and others unhappy with all this dehumanized progress, as symbolized by a gargantuan Space Gun built to shoot the first manned vehicle around the moon. (This was an old Jules Verne device that Wells in '36 must have known was scientifically ludicrous, but it looked great.) Theotocopulos calls for a revival of the olden days when life was "short and hot and merry" (when that was, or what he considers "hot and merry," he doesn't say).

On a building-sized television screen, he rails against the "evil gods" of progress, which must be halted by destroying the Space Gun.

Fortunately, the leader of Everytown is John Cabal's great-grandson, Oswald (Massey again), whose daughter Catherine (Pearl Argyle) is one of the two lunar-bound space pioneers. Her astro-companion is Maurice (Kenneth Viliers), whose father, Raymond Passworthy (Edward Chapman), is Oswald's friend who shares the fears spoken by Theotocopulos.

Oswald learns that Theotocopulos will lead an attack against the Space Gun. Choosing to continue the launch, Catherine and Maurice join Oswald and Passworthy in a helicopter to the launch complex. Theotocopulos keeps on rousing the rabble, who flock to the Space Gun with metal clubs like villagers from a Frankenstein film. Just in the nick of time, the bullet-like moonship is loaded into the launcher and blasted into space. (The fate of the dissidents nearest the "shock wave" is, probably mercifully, not revealed.)

Having grown up with space travel and exploration as a now almost humdrum reality, it's easy for us today to forget that in 1936 the notion was so much fairy-tale fantasy, even among science and rocket enthusiasts. Only the readers of the sci-fi pulp zines gave the notion any credence, and you know what they're like. Even 20 years later, in 1956, Astronomer Royal Richard Woolley decreed in Time magazine that space travel "is utter bilge." (Sputnik was launched the following year, the Apollo Program five years later.)

So this climax may be the most "visionary" element in Things to Come, and Wells gives it appropriate symbolic gravitas. In the movie's most famous sequence, Oswald and Passworthy stand before a huge vision screen spackled with the infinite starry cosmos. Oswald calls it a beginning, but Passworthy wonders if humans are nothing more than animals. Oswald declares that the choice is ours to make, although it's obvious that to Wells the answer is implicit in the question:

"For Man, no rest and no ending. He must go on, conquest beyond conquest. First this little planet with its winds and ways, and then all the laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him and at last out across immensity to the stars. And when he has conquered all the deeps of space and all the mysteries of time, still he will be beginning.... If we're no more than animals, we must snatch each little scrap of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more than all the other animals do or have done. Is it this? Or...all the universe?.... Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be?"

There's no denying that Things to Come is majestic and earnest. Its sequences that burst their seams with science-fictional images are fascinating to watch, especially with one eye on cinematic heritage à la Fritz Lang's Metropolis (which Wells called, with no sense of irony, "the silliest of films").

|

| Wells, Pearl Argyle, Raymond Massey |

The passing years have only added to the film's retro-future kitsch and to the frayed edges of its timeworn period milieu, such as its casual sexism and all-white utopia.

Nevertheless, for boldness of ambition and nobility of purpose, Things to Come stands tall in the canon of science fiction on screen. It's eyebrow-raising in its prescient depiction of the Blitz bombings of London in 1940 and of the war that followed. The Boss remains all too familiar today, whether in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, or here in the U.S. (Perhaps the universe's perverse sense of humor made it inevitable that when the real 1970 came around we had Nixon and Vietnam.)

The film's visual magnitude, episodic structure, and emotional coldness make it an ancestor of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, another slow-moving, characterization-free exploration of Big Ideas. Wells' high-minded epilogue for Massey remains a fine summation of the drives behind some of the best science fiction. Its closing benediction of space travel as the ultimate metaphor for human transcendence continues to sing, even as we're yanked forward into a disquietingly unpredictable 21st century.

For more about the film — a lot more — I recommend the Things to Come website and blog of Nick Cooper. I've never met Nick, but I believe him when he says that his quest for all things Things to Come is an "incurable obsession." Indeed, it pegs the red zone of the Obsessometer, and I raise my glass of Bushmill's to him for it.

He covers areas I've elected to not go into here, such as the footage that has been indelicately snipped or re-edited over the decades. (The most common edition these days — embedded below — is just shy of 93 minutes, while the original theatrical release clocked in at 130 minutes, a cut of almost 30%.) Nick's coverage of the excised footage includes imagery and script reproductions. His collection of advertising and promo material is likewise impressive.

Cooper also provides an audio commentary track on the UK DVD edition released in 2007, which seems to be the best DVD edition of the film currently available. My old pal Glenn Erickson (a.k.a "DVD Savant") provides a thorough look at that DVD at his site.

* Thomas C. Renzi, in his H.G. Wells: Six Scientific Romances Adapted for Film, quotes Wells' own notes about his rather unsatisfying apprenticeship in writing for the screen.

Music: Melody Gardot (mmmmm)

Near at hand: A shelf full of Donald Harington novels, which I've had a hankerin' to revisit lately.